Three artists have been commissioned to create the first wave of installations for the Los Angeles County Museum of Art’s new David Geffen Galleries, scheduled to open in April next year. The expansive site-specific works will help to define the look and feel of the Peter Zumthor-designed building, and in the case of one artwork — a 75,000-square-foot stretch of embellished and brushed concrete — literally provide the ground on which visitors walk.

The artists — Mariana Castillo Deball, Sarah Rosalena and Shio Kusaka — were all picked based on their previous work at LACMA and for how themes espoused in their art, including land rights and a fascination with the cosmos, fit with the ethos of the new building’s modernist design.

“I have a rule in my life: If you get stuck, you ask people for advice. If you get really stuck, you ask an artist,” said LACMA President and Chief Executive Michael Govan during a recent visit to the site, where Castillo Deball was immersed in crafting her piece, “Feathered Changes.”

The idea for Castillo Deball’s commission rose from the question of what to do around the 900-foot-long concrete building, which curves over Wilshire Boulevard and is outfitted with floor-to-ceiling glass. Traditional landscape architecture wasn’t cutting it, Govan said, and he kept thinking about the idea of a map on the ground.

A detail of artist Mariana Castillo Deball’s “Feathered Changes,” a commission for LACMA’s David Geffen Galleries.

(Mariana Castillo Deball)

“Feathered Changes” serves as the museum plaza floor and occupies an area roughly the size of three football fields. It forms a series of concrete islands leading to various entrances and extends through the restaurant. The piece, which is characterized by an earth-colored mix of unfinished concrete that both complements and contrasts with the building, is imprinted with pieces of Castillo Deball’s feathered serpent drawings inspired by ancient murals from Teotihuacán, Mexico. Other areas are raked in patterns resembling a Zen garden, and some contain replica tracks of native animals, including coyotes, bears and snakes. Small stones have been cast into the mix, creating a rough, uneven color and texture.

“This is the biggest challenge I’ve had in my life,” Castillo Deball said after using a custom rake to carve wet concrete at the base of the building. Concrete workers swarmed around her in hardhats. “It’s a place that is gonna be totally public, so everybody can go in and step on it,” she said. “It’s a very democratic piece of art that is also in dialogue with this amazing building, with the collection, with the curators.”

Castillo Deball, who splits her time between Mexico City and Berlin, is no stranger to large-scale, L.A.-based projects. She created four landscape-focused collages for the concourse level of Metro’s Wilshire/La Cienega station. But the LACMA commission is by far the biggest piece of art she has made, and she said she’s learned a great deal from the process.

“I feel like an engineer,” she said, smiling from under her hardhat. “I never knew so much about concrete and rebar.”

Castillo Deball also relishes collaborating with the team of specialized workers employed to assist her in pouring — and taming — the tricky cement.

“They’re all Mexican. They come from Jalisco, and we communicate in Spanish,” she said. “And they always ask me, what am I doing? What does it mean? And then a lot of solutions, we also develop them together. And they’re so curious and proud that a Mexican artist is doing something like this.”

The building, which has asymmetrical overhead lighting resembling stars, represents the sky, Govan noted, and Castillo Deball’s artwork tethers the building to the land.

“All the other ground solutions seemed mechanical,” Govan said.

Sarah Rosalena, from left, Mariana Castillo Deball and Shio Kusaka were selected to create new works based, in part, on how themes espoused in their art fit with the ethos of the modernist design of the new David Geffen Galleries.

(Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

Govan had recently flown in from Tilburg in the Netherlands, where he visited the TextielMuseum’s TextielLab with interdisciplinary artist and weaver Sarah Rosalena. Her commission — an 11-by-26½-foot tapestry invoking the ethereal topography of Mars — was being woven on one of the largest Jacquard looms in the world. A few weeks later, a test swath of the tapestry was shipped to LACMA so Rosalena could see how colors and materials looked and felt.

“I was really interested in pushing the textile to really think about terrain,” said Rosalena, standing over the tapestry, which was laid out on a long conference table in a nearby office tower with a bird’s-eye view of the new building. “So that’s experimenting with different yarns. Some of it looks like clouds. Some of it almost looks like ocean or water. Some of it looks atmospheric, but definitely otherworldly.”

Rosalena is an Angeleno of Wixárika heritage whose practice merges ancient Indigenous craft with computer-driven science and technology to challenge colonial narratives and examine global problems such as climate change and cultural hegemony. She has fond memories of watching her grandmother weave on a backstrap loom while growing up in La Cañada Flintridge, and found that she was just as skilled at computer programming as she was at making textiles.

Sarah Rosalena’s 26-foot long weaving, “Omnidirectional Terrain” (2025), in progress on the jacquard-rapier loom at TextielLab in Tilburg, Netherlands.

(Alexandra Ross)

“My mother would also do a lot of weaving and beading,” said Rosalena, a professor at UC Santa Barbara. But it wasn’t until she got interested in photo and digital media processes that she saw their relationship to weaving.

When it’s complete, the tapestry, “Omnidirectional Terrain,” will hang on the 30-foot wall in the museum restaurant, where it will be visible through the glass that looks in from the courtyard and Castillo Deball’s “Feathered Changes.” The patterns that Castillo Deball will have created underfoot will run beneath Rosalena’s work — the earth beneath a mercurial red sky.

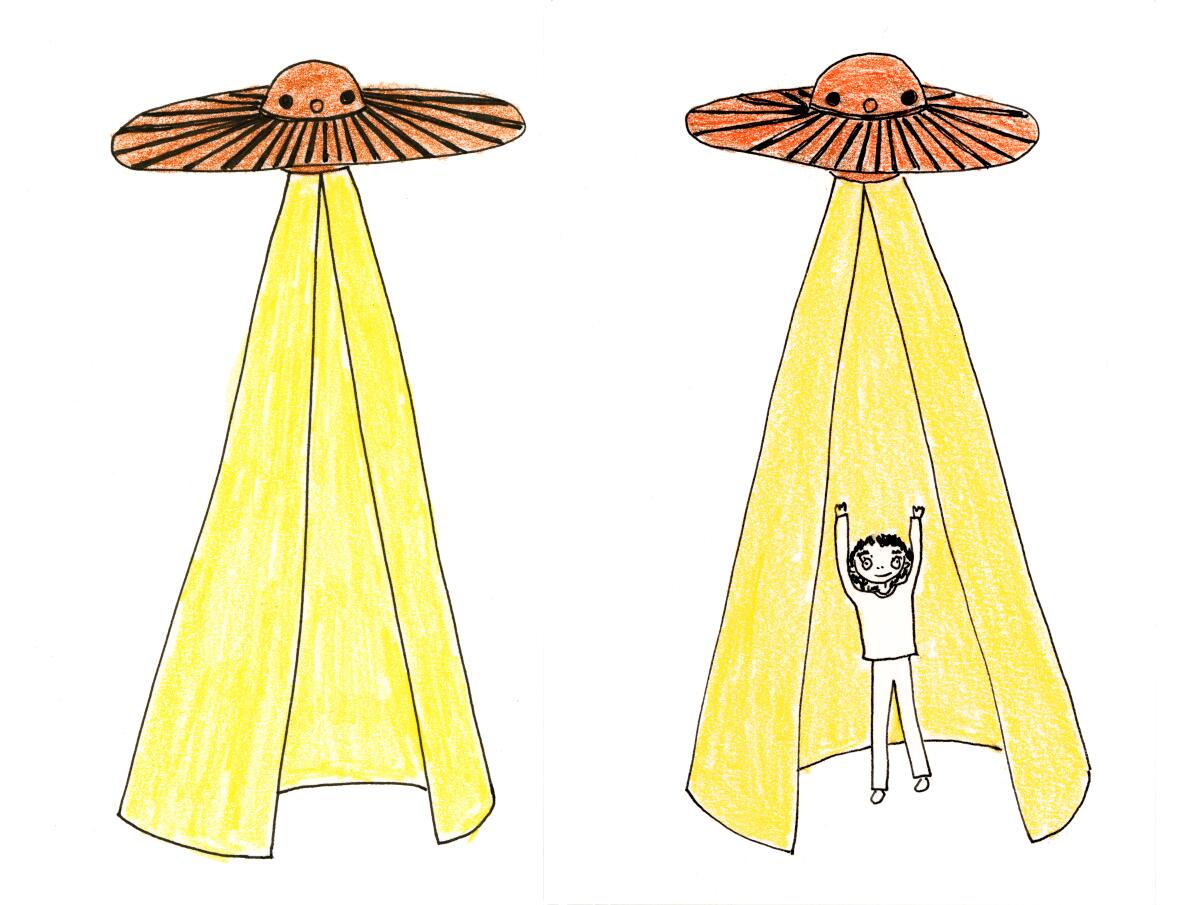

The third commission, by ceramicist Kusaka, will be around the corner from the first two, in a plaza. Kusaka laid out a series of drawings on small white pieces of paper on the conference table, tracing the evolution of her idea from a basic sketch to what she hopes will be its final iteration: a 12-foot-tall interactive sculpture featuring a flying saucer atop a cone of bright light, which children and adults can enter, ostensibly to be beamed up to the craft — if only for a fun photograph.

“When students are in the education center, they’re looking through glass at it, which will be a nice inspiration,” Govan said. “You’ll also see it as you’re on Wilshire. What is that interesting thing? So that was the idea.”

Preparatory sketches for Shio Kusaka’s LACMA-commissioned sculpture. The second includes a figure to show scale.

(Shio Kusaka)

Creating visitor attractions that can be shared on social media has proved a savvy marketing strategy at LACMA, where Chris Burden’s “Urban Light” installation of city streetlamps and Michael Heizer’s “Levitated Mass,” often referred to as the Rock, have grown from Instagram moments to beloved civic landmarks.

Kusaka’s playful forms are most commonly seen in her ceramic pots, vases and vessels, often glazed with bright colors and decorated with whimsical geometric patterns. Her obsession with space and space creatures finds its lineage in some pots she shows from a book of her work. Some have buttons resembling the control panel of a spaceship; others have little faces that could be alien.

“I don’t like making big things for no reason. I really like small things I can hold,” Kusaka said. “But it’s really fun to have a reason that I can go this big, which might be a part of why I want a person to go inside.”

Kusaka was born in Japan and learned traditional crafts from her grandparents. Her grandmother taught tea ceremonies, and her grandfather taught calligraphy.

“I never thought that I was gonna relate to what they did at the time. But I do see the relationship now,” said Kusaka, explaining how she began her study of ceramics in college in Boulder, Colo. “So I was touching ceramics a lot, and then I learned how to look at tools and to appreciate their functions.”

Her fanciful commission for LACMA charts a new course, but in a way, she said, it’s still a vessel.