Hamburg train station, September 1933 – the scene for a farewell between two long-time team-mates who achieved so much together.

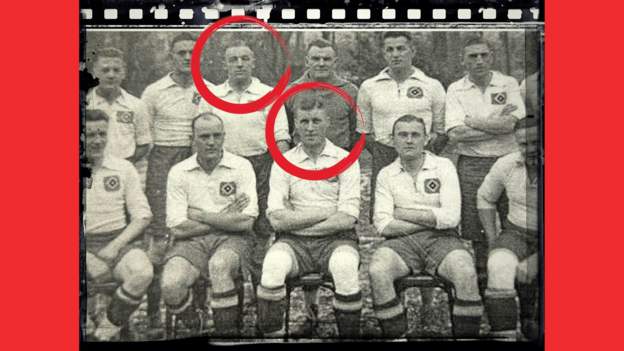

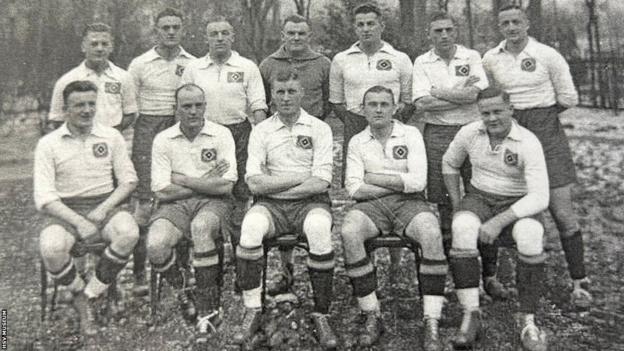

Asbjorn Halvorsen was heading home to Norway. A midfielder with Hamburg, he had been a key part of their attack and one of German football’s first foreign stars. The other man – Otto Fritz ‘Tull’ Harder – had been the beneficiary of Halvorsen’s creativity. A clinical finisher with the strength of a removal man, Harder’s goals had powered Hamburg to German titles in 1923 and 1928.

Harder had rushed to the station on an impulse to thank Halvorsen for their time together and wish him well. Neither knew, at that point, the dramatically different tracks their lives were taking.

Now 34, Halvorsen was retiring from football to take up a role with the Norwegian Football Association. He would lead their national team to a bronze medal at the 1936 Olympics in Berlin – still the country’s only international football honour.

But his name is remembered best for what happened next. When World War Two engulfed Europe, Halvorsen fought against Norway’s Nazi occupiers as a member of the resistance before being captured and sent to concentration camps.

Harder was six years older than Halvorsen. As the political and military picture transformed in Germany, he joined the SS. It was a part of the Third Reich that was both feared and revered. Originally Adolf Hitler’s personal protection unit, it had expanded to take charge of eliminating the Nazis’ political and racial targets.

Harder rose through the ranks, eventually becoming commander at one of the concentration camps Halvorsen would be sent to.

It is not believed they met again. By the time Halvorsen arrived at Harder’s Neuengamme camp in April 1945, his former team-mate had been ordered elsewhere. But the conditions he suffered were moulded by Harder’s hands. And Halvorsen’s death, in June 1955, was probably because of the consequences of the typhus illness he caught in the camps.

Jurgen Kowalewski is a retired history teacher from Hamburg who has researched Halvorsen’s life as a two-year project together with his students. They have visited the concentration camp memorial, Halvorsen’s former houses in Hamburg and his hometown club in Norway.

“We are still fighting to name a street in Hamburg after him,” Kowalewski says.

Those efforts have so far been in vain – though Halvorsen’s remarkable story deserves to be better known.

Aged 18, Halvorsen captained and scored for his hometown club Sarpsborg in their 1917 Norwegian Cup final victory, beating Brann Bergen 4-1.

During those amateur days he was working as a ship broker. An opportunity came to move to Germany’s north coast.

He joined Hamburg and was an immediate success – Halvorsen led the club to two German championships and eight regional north German championships.

In the book ‘A-laget’ about the greatest Norwegian football personalities, the authors claim there was even an offer for Halvorsen to join the German national team as captain, if he had been open to changing his nationality. He is said to have refused it.

For a long time though he had been better known in Germany than in the country of his birth.

Why he chose to board that train, bid farewell to Harder and leave Germany in September 1933 is still unclear.

“I would doubt that he left Germany because of the political situation,” history teacher Kowalewski says.

“We have no evidence of him opposing the people in power until 1940, when he was back in Norway.”

According to a report in Norwegian football magazine Josimar, Halvorsen was the only player to keep his hands by his sides while team-mates performed a Nazi salute in a testimonial match played in his honour just before his departure.

But Halvorsen returned to Germany three years later, managing the Norway team at the Berlin Olympics of 1936. In the quarter-finals, Norway were underdogs against a host nation playing against a backdrop of propaganda proclaiming racial superiority.

After Germany had defeat Luxembourg 9-0 in the previous round, Hitler, ambivalent about football, was persuaded to attend the match. The expected German rout never came. Norway won 2-0 and Hitler was said to have furiously abandoned his seat before the final whistle.

Norway lost to eventual winners Italy 2-1 after extra time in the semi-finals, but Halvorsen was praised for his match analysis and approach to player nutrition, which was advanced for the time.

As a coach, Halvorsen was charismatic and innovative. At a banquet at the 1938 World Cup in France, he performed a dance from the then-popular musical Me And My Girl in front of players and staff.

In April 1940 the Nazis invaded Norway, and the occupiers also wanted to put the Football Association under their control. Halvorsen, who was not only national team manager but also head of the FA, is said to have written a letter in protest.

Before that year’s Norwegian Cup final, he also tried to prevent Nazi commanders from taking position and lifting swastika flags among the VIP seats, an area usually reserved for the Norwegian royal family, who had fled into exile.

“Halvorsen played a massive part in an underground sport organisation that became an important resistance group in Norway,” Kowalewski says.

“They boycotted the Nazis and even sabotaged those few who did participate in Nazi sport events, for example by sprinkling sand on ice rinks by night.”

Halvorsen’s opposition went beyond sport, though.

In August 1942, the Nazis searched a small basement in Oslo and discovered a covert resistance operation.

The basement contained a printing press that produced Bulletinen and Whispering Times – newspapers that distributed information from British radio broadcasts among the suppressed population.

The Nazis arrested Halvorsen immediately.

“He had proposed to pool the illegal newspapers together,” a note of the SS stated.

Halvorsen was imprisoned in Norway for almost a year. “I am hungry. And I fear I am going to be deported to Germany,” he wrote in a letter to his brother Olaf.

His fears were justified.

When he was taken away, those who came for him were following the Nazis’ clandestine Nacht und Nebel – Night and Fog – directive, an operation that sought to capture resistance members and leave no trace of them behind.

Halvorsen was deported to a concentration camp in Natzweiler, near the Vosges mountains in annexed eastern France. Prisoners had to work in the quarry and in road construction, among other physically demanding tasks.

According to Norwegian magazine Josimar only 266 of the 504 Norwegian prisoners in the camp survived. The high death-rate was due to the brutality of the guards, malnourishment and illness. As a former footballer, Halvorsen was well known by some of the guards and is said to have received some beneficial treatment, which he sought to share among his fellow inmates.

In September 1944, Halvorsen was relocated to Neckarelz, to the south of Frankfurt, where a former school building had been converted into another camp.

In January 1945 he was moved again to a so-called sickbed at a camp near Vaihingen, a little further south.

“It was a paradox to describe it as a sickbed; it was filthy and full of lice,” then-prisoner Kristian Ottosen wrote in his diary.

Ottosen also describes how Halvorsen became an informal representative of the other inmates and successfully applied for more food. Other contemporary accounts describe how Halvorsen was tortured after refusing to hit another prisoner when ordered to by the guards.

In April 1945, Halvorsen was again sent to another camp, Neuengamme, on the outskirts of Hamburg where he had once been a star. Only a few months before, his old team-mate Harder had been the commanding officer.

Halvorsen was fighting famine and illness. He was suffering from epidemic typhus, a disease spread through contact with infected body lice. Conditions at Harder’s Neuengamme were as miserable – if not worse – than those Halvorsen had previously been held in.

“Even compared to the condition in other camps, it was excruciating there,” the Allied High Commission would later deem, as it sought to prosecute those responsible following the defeat of Nazi Germany.

At least 42,900 people died at Neuengamme, many through exhaustion as they were subjected to hard labour and meagre rations. It was also the site of deadly medical experiments on prisoners, including children.

Harder was sentenced to 15 years imprisonment for the war crimes he committed while in charge of the camp. He spent only four years behind bars before dying aged 63 in March 1956.

It is uncertain whether he and Halvorsen’s paths crossed again after the war.

Halvorsen was rescued by the Red Cross in April 1945, but at first was too emaciated and weak to be transported on one of the aid organisation’s buses.

In an interview with newspaper Aftenposten later that year he said: “Starving is the cruellest thing. The sucking in the stomach is nearly unbearable and we did the most incredible things to numb the ache.”

It was late May or June when Halvorsen finally returned to Oslo. On the way, he promised free tickets to Norway’s next international to fellow prisoners of war transported with him.

After the war, Halvorsen returned to sport as the Norwegian Football Association’s general secretary and, among other improvements, set up a new league system with better progress between the divisions.

When Norway played in Germany during qualifying for the 1954 World Cup, Halvorsen travelled with the team. Yet again, fate took him to Hamburg.

German sports magazine Kicker reported a meeting between Halvorsen, West Germany manager Sepp Herberger and Georg Xandry of the German Football Association, where all three shook hands, to which reporters concluded: “All that had occurred, it was forgotten.”

German political scientist Arthur Heinrich has since said the German public desperately wanted to put an end to discussions of the Nazi horrors, and that these reports might exemplify a broader intention in society back then.

“We shouldn’t mix up forgiving or forgetting,” former teacher Kowalewski says. “Soon after the war, Halvorsen became a silent man in regards of what had happened.

“But he really engaged himself in helping German athletes take part in the Winter Olympics in Oslo in 1952, which a lot of his fellow citizens opposed. He said that athletes weren’t responsible and shouldn’t be punished. That was a sign of grace. Maybe Halvorsen also felt a connection to the country he had been living in for twelve years.”

Indeed, Halvorsen would have been constantly reminded of the tortures and maltreatment he had suffered. He died in June 1955, while on a work trip for the Norwegian FA, his health having been permanently weakened by the typhus he caught during his time in concentration camps.

“It was the time in the camps that ruined his health and lead to his death,” said Yngvar Steen, long-time historian at Sarpsborg, Halvorsen’s first club.

“When I held a speech on Halvorsen at the 100th birthday celebrations of our club, I sensed that only a few members knew his name.

“I hope that changes, because he deserves uncountable credit and recognition.”