A battle is underway against an invasive mosquito behind a recent surge in the local spread of dengue fever in Southern California — and officials may have unlocked a powerful tool to help win the day.

Two vector control districts — local agencies tasked with controlling disease-spreading organisms — released thousands of sterile male mosquitoes in select neighborhoods, with one district starting in 2023 and the other beginning the following year.

The idea was to drive down the mosquito population because eggs produced by a female after a romp with a sterile male don’t hatch. And only female mosquitoes bite, so unleashing males doesn’t lead to transmission of diseases such as dengue, a potentially fatal viral infection.

The data so far are encouraging.

One agency serving a large swath of Los Angeles County found a nearly 82% reduction in its invasive Aedes aegypti mosquito population in its release area in Sunland-Tujunga last year compared with a control area.

Another district, covering the southwestern corner of San Bernardino County, logged an average decrease of 44% across several heavily infested places where it unleashed the sterile males last year, compared with pre-intervention levels.

Overall invasive mosquito counts dropped 33% across the district — marking the first time in roughly eight years that the population went down instead of up.

“Not only were we out in the field and actually seeing good reductions, but we were getting a lot less calls — people calling in to complain,” said Brian Reisinger, community outreach coordinator for the Inland Empire’s West Valley Mosquito and Vector Control District.

But challenges remain. Scaling the intervention to the level needed to make a dent in the vast region served by the L.A. County district won’t happen overnight and would potentially require its home owners to pay up to $20 in an annual property tax assessment to make it happen.

Climate change is allowing Aedes mosquitoes — and diseases they spread — to move into new areas and go gangbusters in places where they’re established.

Surging dengue abroad and the widespread presence of Aedes mosquitoes at home is “creating this perfect recipe for local transmission in our region,” said Dr. Aiman Halai, director of the vector-borne disease unit at the L.A. County Department of Public Health.

Tiny scourge, big threat

Aedes aegypti mosquitoes were first detected in California about a decade ago. Originally hailing from Africa, the species can transmit dengue, as well as yellow fever, Zika and chikungunya.

Another invasive mosquito, Aedes albopictus, arrived earlier, but its numbers have declined and it is less likely to spread diseases such as dengue.

Although the black-and-white striped Aedes aegypti can’t fly far — just about 150 to 200 yards — they manage to get around. The low-flying, day-biting mosquitoes are present in more than a third of California’s counties, including Shasta County in the far north.

An Aedes mosquito, known for nipping ankles, prefers to bite humans over animals. The insects, which arrived in California about a decade ago, can transmit diseases such as dengue and Zika.

(Orange County Mosquito and Vector Control District)

Aedes mosquitoes love to bite people — often multiple times in rapid succession. As the insects spread across the state, patios and backyards morphed from respites into risky territories.

But tamping down the bugs has proved difficult. They can lay their eggs in tiny water sources. And they might lay a few in a plant tray and others, perhaps, in a drain. Annihilating invaders isn’t easy when it can be hard to locate all the reproduction spots — or access all the yards where breeding is rampant.

That’s one of the reasons why releasing sterilized males is attractive: They’re naturally adept at finding their own kind.

Mosquito vs. mosquito

Releasing sterilized male insects to combat pests is a proven scientific technique that’s been around since the 1950s, but using it to control invasive mosquitoes is relatively new. The approach appears to be catching on in Southern California.

The West Valley district pioneered the release of sterilized male mosquitoes in California. In 2023, the Ontario-based agency rolled out a pilot program before expanding it the following year. This year it is increasing the number of sites being treated.

The Greater Los Angeles County Vector Control District launched its own pilot effort in 2024 and plans to target roughly the same area this year — with some improvements in technique and insect-rearing capacity.

Starting in late May, an Orange County district will follow suit with the planned release of 100,000 to 200,000 sterile male mosquitoes a week in Mission Viejo through November. A Coachella Valley district is plugging away at developing its own program, which could get off the ground next spring.

Vector officials in L.A. and San Bernardino counties said residents are asking them when they can bring a batch of zapped males to their neighborhood. But experts say for large population centers, it’s not that easy.

“I just responded this morning to one of our residents that says, ‘Why can’t we have this everywhere this year?’ And it’s, of course, because Rome wasn’t built in a day,” said Susanne Kluh, general manager for the Greater Los Angeles County Vector Control District.

Kluh’s district has a budget of nearly $24 million and is responsible for nearly 6 million residents across 36 cities and unincorporated areas. West Valley’s budget this fiscal year is roughly $4 million, and the district serves roughly 650,000 people in six cities and surrounding county areas.

Approaches between the two districts differ, in part due to the scale they’re working with.

West Valley targets what it calls hot spots — areas with particularly high mosquito counts. Last year, before peak mosquito season, it released about 1,000 sterile males biweekly per site. Then the district bumped it to up to 3,000 for certain sites for the peak period, which runs from August to November. The idea is to outnumber wild males by 100 to 1. Equipment for the program cost about $200,000 and the district hired a full-time staffer to assist with the efforts this year for $65,000.

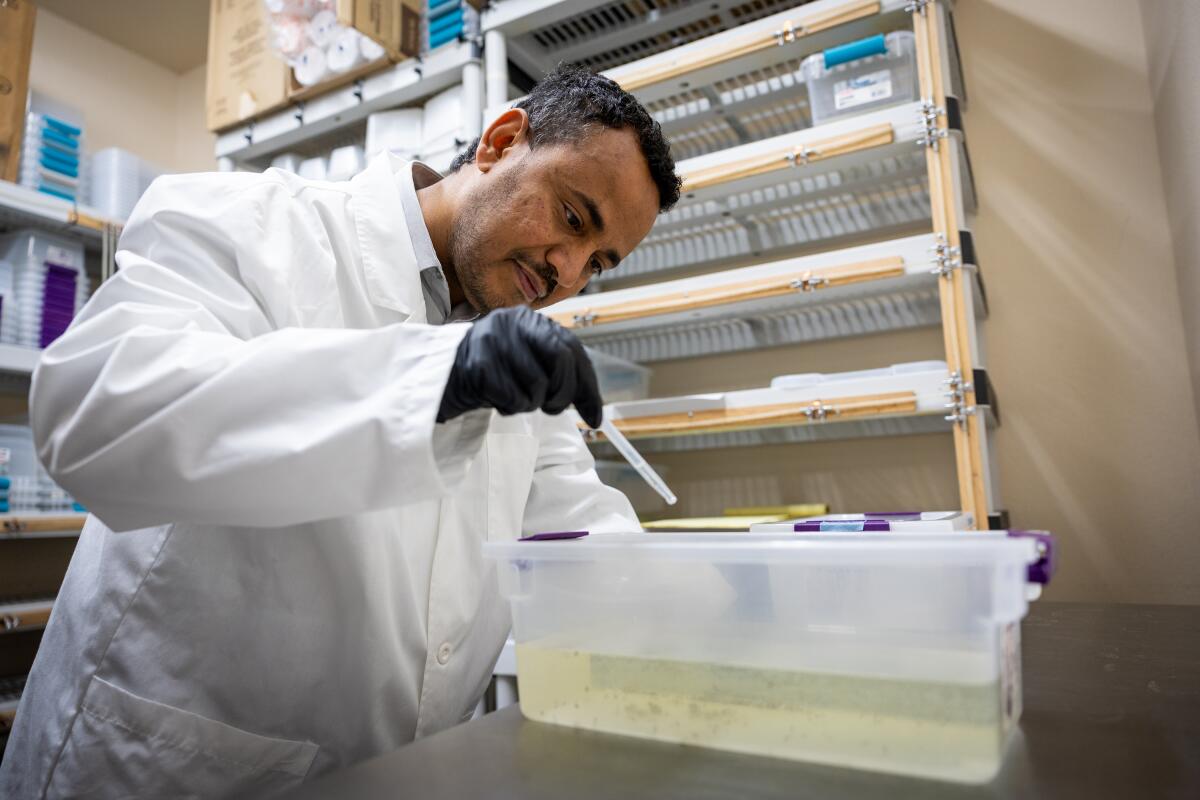

Solomon Birhanie, scientific director for West Valley, said the district doesn’t have the resources to attack large tracts of land so it’s using the resources it does have efficiently. Focusing on problem sites has shown to be sufficient to affect the whole service area, he said.

“Many medium to smaller districts are now interested to use our approach,” he said, because there’s now evidence that it can be incorporated into abatement programs “without the need for hiring highly skilled personnel or demanding a larger amount of budget.”

Solomon Birhanie, scientific director at the West Valley Mosquito and Vector Control District, views a container of mosquito larvae in the lab in March 2024. The Ontario-based district pioneered the release of sterilized male Aedes mosquitoes in California.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

In its inaugural study last year, the L.A. County district unleashed an average of 30,000 males per week in two Sunland-Tujunga neighborhoods between May and October — seeking to outperform wild males 10 to 1. Kluh anticipates this year’s pilot will cost about $350,000.

In order to bring the program to a larger area of the district, Kluh said more funding is needed — with officials proposing up to $20 annually per single-family home. That would be in addition to the $18.97 district homeowners now pay for the services the agency already provides.

If surveys sent to a sample of property owners favor the new charge, it’ll go to a vote in the fall, as required by Proposition 218, Kluh said.

There are five vector control districts that cover L.A. County. The Greater L.A. County district is the largest, stretching from San Pedro to Santa Clarita. It covers most of L.A. city except for coastal regions and doesn’t serve the San Gabriel or Antelope valleys.

Galvanized by disease

California last year had 18 locally acquired dengue cases, meaning people were infected with the viral disease in their communities, not while traveling.

Fourteen of those cases were in Los Angeles County, including at least seven tied to a small outbreak in Baldwin Park, a city east of L.A. Cases also cropped up in Panorama City, El Monte and the Hollywood Hills.

The year before that, the state confirmed its first locally acquired cases, in Long Beach and Pasadena.

Although most people with dengue have no symptoms, it can cause severe body aches and fever and, in rare cases, death. Its alias, “breakbone fever,” provides a grim glimpse into what it can feel like.

Over a third of L.A. County’s dengue cases last year required hospitalization, according to Halai.

Mosquitoes pick up the virus after they bite an infected person, then spread it by biting others.

Hope and hard truths

Mosquito control experts tout sterilization for being environmentally friendly because it doesn’t involve spraying chemicals and officials could potentially use it to target other disease spreaders — such as the region’s native Culex mosquito, a carrier of the deadly West Nile virus.

New technologies continue to come online. In the summer last year, the California Department of Pesticide Regulation approved the use of male mosquitoes infected with a particular strain of a bacteria called Wolbachia. Eggs fertilized by those males also don’t hatch.

Despite the promising innovations, some aspects of the scourge defy local control.

Since her start in mosquito control in California nearly 26 years ago, Kluh said, the season for the insects has lengthened as winters have become shorter. Back then, officials would get to work in late April or early May and wrap up around early October. Now the native mosquitoes emerge as early as March and the invasive insects can stick around into December.

“If things are going the way it is going now, we could just always have some dengue circulating,” she said.

Last year marked the worst year on record for dengue globally, with more than 13 million cases reported in the Americas and the Caribbean, according to the Centers for Disease Control.

Many countries are still reporting higher-than-average dengue numbers, meaning there’s more opportunity for travelers to bring it home.