Before the fence, there was the lizard.

From tree stumps and rocks, the spiny reptiles basked and watched as wooden fences subdivided the landscape. At some point, one climbed a post and became known to us ever onward as the fence lizard.

If you grew up or live in California or western United States, chances are you’ve seen sceloporus occidentalis.

According to a leading dataset of animal and plant observations, the fence lizard is the most commonly spotted reptile in the U.S.; and the top species in California. Why?

The answer reflects how humans have invaded its space and how it has adapted to ours. At first glance, it’s not much to look at. Dull brown. Immobile. Just a lizard.

“Because they’re so common, people assume they’re quite boring,” said Breanna Putman, an ecologist at Cal State San Bernardino.

Yet, something magical happens when you spot one. It’s both an ordinary occurrence and an event. One that makes you stop and say, “Look, a lizard!”

Western fence lizards are a common sight in Southern California yards.

(Dania Maxwell / Los Angeles Times)

Though fence lizards don’t hibernate, they become sluggish in winter, which is why these days, warmed by the sun and driven by the urge to mate, they’re once more appearing all over. With the 10th City Nature Challenge — a four-day “bioblitz” competition to document urban animals and plants — beginning this week, now seems the perfect time to celebrate our friendly neighborhood fence lizard.

One of the largest platforms for sharing observations of animals and plants is iNaturalist. Think of it as the social network for nature nerds.

The app’s 3.5 million global users post photos of fauna and flora from anywhere fauna and flora are found — urban parks, suburban backyards, mountaintops.

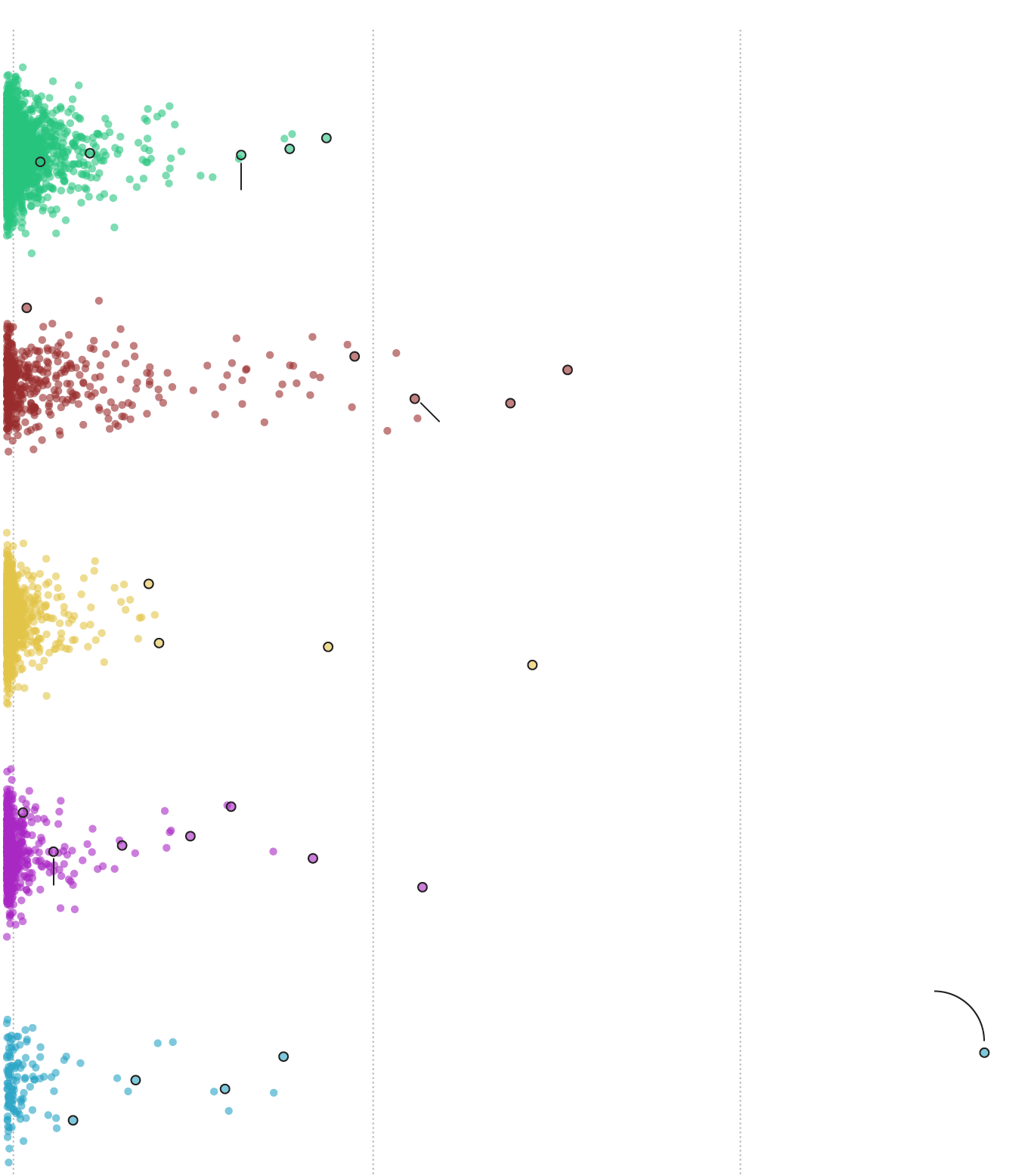

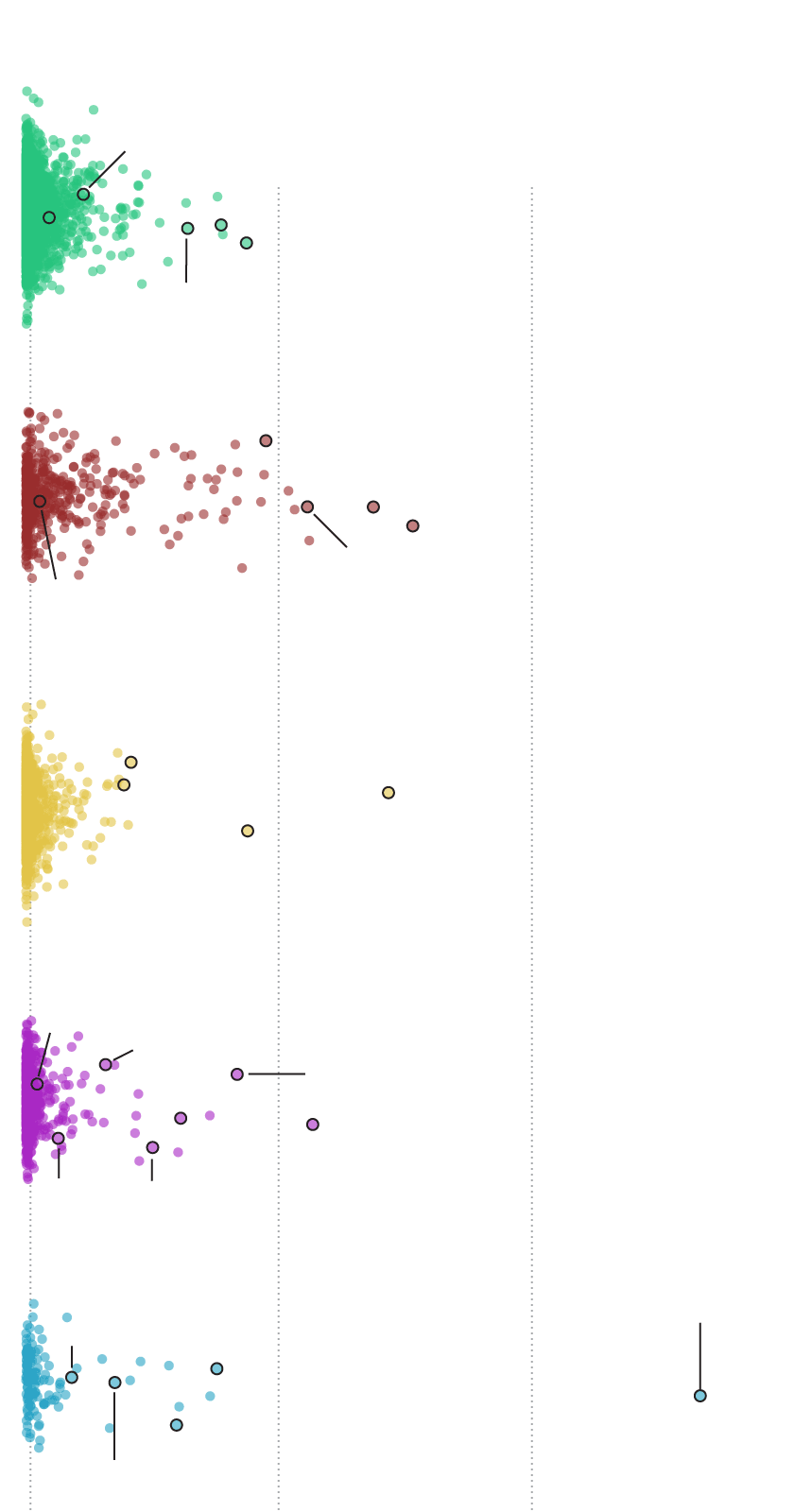

Each dot represents a species observed in iNaturalist. The more observations it has, the closer it is to the center of the circle.

In California, more than 26,000 species have been documented and confirmed on the platform, the majority of which are plants and fungi.

Most species go unnoticed. Around 90% of species in the state have been observed fewer than 500 times. But the fence lizard stands out.

For every observation of a California poppy or a ground squirrel, there are three western fence lizards. For every red-tailed hawk, there are nearly two lizards.

With more than 130,000 verified identifications in the state, the fence lizard is the center of attention.

No one has recorded more fence lizards on iNaturalist than Jim Maughn.

Maughn, an English professor from Santa Cruz, began using the app over a decade ago when he started taking daily five-mile walks. Inevitably, a fence lizard is waiting for him.

Since 2013, he has logged some 1,900 of the platform’s nearly 150,000 S. occidentalis observations.

“They’re hard to miss,” Maughn said. “If you go out in nature and just sort of let your eyes go out ahead of you, you’re probably going to see a lizard at some point.”

If you happen to spot a fence lizard, look closely. Especially in springtime, you’ll find some have vibrant blue patches brightening their stomachs and throats, hence their other name: “blue bellies.”

“They can be really strikingly blue, from a turquoise to a bright royal blue,” Putman said. “When people touch them, it’s kind of cool because their bellies are soft and smooth. Their backs are sharp and spiny. It’s kind of analogous to sharkskin.”

“It’s a species that wants to be seen,” said Greg Pauly, the head of herpetology at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County.

Western fence lizards are California’s most observed species on iNaturalist

Plants, fungi and lichens

Seven-spotted

lady beetle

Mammals and other animals

California ground squirrel

Common side-blotched lizard

Southern alligator lizard

Plants, fungi and lichens

Seven-spotted lady beetle

Mammals and other animals

California ground squirrel

Common side-blotched lizard

Southern alligator lizard

LOS ANGELES TIMES

Unlike birds or frogs that broadcast their presence with sound, blue bellies communicate visually. Males choose conspicuous basking locations — a rock, stucco wall or, well, a fence — to woo females and proclaim ownership of a territory. If another male approaches, the presiding reptile will do “push-ups” to assert dominion over its realm. They may even do battle.

A western fence lizard performs its push-up display in Griffith Park. (Sean Greene / Los Angeles Times)

This territoriality makes it easier for human observers to get relatively close to them. In a 2017 study led by Putman and Pauly, researchers were better able to approach and capture the lizards if they were wearing blue shirts.

The males’ showiness might help attract females, but their displays can draw the attention of cats, birds and other potential predators.

“So being apparent is sort of a double-edged sword,” said Robert Espinoza, a herpetologist at Cal State Northridge. “You may get the mates, but you’re also exposing yourself to predators.”

“Beauty has a price,” said herpetologist Robert Hansen.

Western fence lizards occur in seven U.S. states and Baja California, but about 90% of S. occidentalis observations on iNaturalist occur in California, suggesting either the species is concentrated here or the large human population provides plenty of eyes on the creatures.

Outside California, iNaturalist users focus on other things. Oregonians enjoy snapping pictures of ponderosa pines. In Washington, it’s mallards — the most commonly observed species worldwide. Nevadans have a thing for creosote bushes.

Since its launch in 2008, iNaturalist has become the largest source of biodiversity information thanks to its broad user base.

Each spring since 2015, Pauly has called upon community scientists to document the mating behavior of alligator lizards, which involves the male holding the female in a bite, sometimes for days.

The project has helped museum staff generate what they believe is the largest dataset on lizard mating, with more than 1,000 observations.

The gold standard of biodiversity research, the structured survey, is designed with rigor and may be limited to a specific time and place. Observations on iNaturalist are almost the complete opposite but can be used to document animals on a massive scale.

“It’s a perfect indication of the fact that we have eyes on a place at that time,” said biologist Giovanni Rapacciuolo.

Common species such as the fence lizard could serve as a benchmark for scientists monitoring rarer or more elusive creatures. The more fence lizard observations you have, the harder people are looking for things. In theory, that means other interesting species would come up in the dataset as well, Rapacciuolo said.

Rapacciuolo said the fence lizard’s overwhelming ubiquity on iNaturalist almost certainly comes down to “what human beings think is cool.” Like a large sunbathing lizard.

“It’s almost definitely not the most common species in California, it’s the most commonly recorded on iNaturalist,” he said. The most common species is probably a plant or insect, he said, but compared with a fence lizard, “they’re not as charismatic or easy to find.”

Fence lizards are sort of a gateway species for nature-watchers, Pauly said.

“Once people start looking at western fence lizards, they start to realize that there are actually lizards in all different places,” he said. “This is especially true for people who have spent most of their lives in cities. You sort of have to learn how to observe wildlife.”

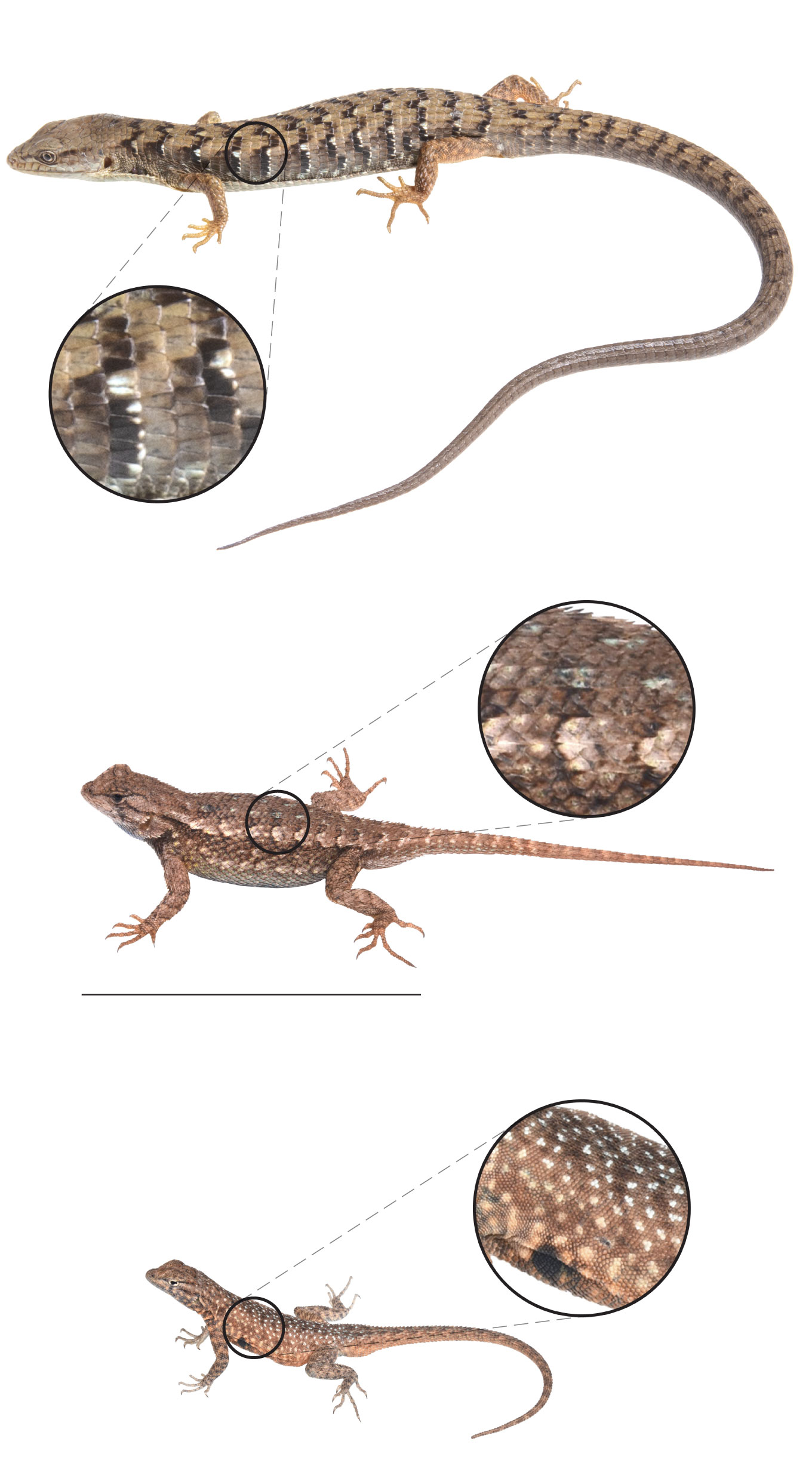

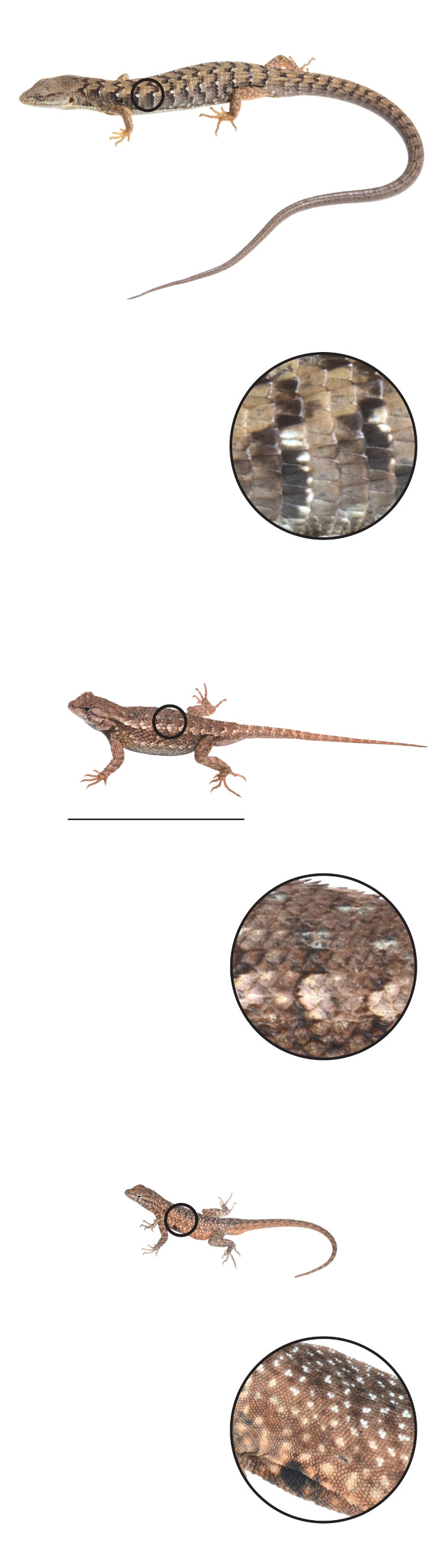

To scale: Know your local lizards

Southern alligator lizard

(Elgaria multicarinata)

Range: Central Washington

into Baja California

Dark bands or chevrons

along back

Tail can as long as

body if unbroken.

Shorter if regrown

Elongated body, up to 7 inches,

not including tail. Short limbs

Western fence lizard

(Sceloporus occidentalis)

Range: Pacific Coast states and Great Basin, including Baja California

Brown, grayish or

nearly black, with darker

markings on back

Blue patches on

throats and bellies

Common side-blotched lizard

(Uta stansburiana)

Range: Western U.S. and

northwestern Mexico

Adult males have blue,

orange and yellow flecks

on back. Females may have

light and dark markings or

white spots.

Up to 2.5 inches,

not including tail

Black spot behind

front limbs

Southern alligator lizard

(Elgaria multicarinata)

Range: Central Washington into Baja California

Dark bands or chevrons

along back

Elongated body, up to 7 inches,

not including tail. Short limbs

Tail can be as long

as body if unbroken.

Shorter if regrown

Western fence lizard

(Sceloporus occidentalis)

Range: Pacific Coast states and Great Basin, including Baja California

Blue patches on

throats and bellies

Brown, grayish or

nearly black, with darker

markings on back

Black spot behind

front limbs

Common side-blotched lizard

(Uta stansburiana)

Range: Western U.S. and northwestern Mexico

Adult males have blue,

orange and yellow flecks

on back. Females may have

light and dark markings or

white spots.

Up to

2.5 inches,

not including tail

Southern alligator lizard

(Elgaria multicarinata)

• Range: Central Washington into Baja California

• Yellow-ish eyes

• Elongated body, up to 7 inches, not including tail. Short limbs

• Tail can be as long as body if unbroken. Shorter if regrown

• Dark bands or chevrons along back

Western fence lizard

(Sceloporus occidentalis)

• Range: Pacific Coast states and Great Basin, including Baja California

• Blue patches on throats and bellies

• Brown, grayish or nearly black, with darker markings on back

Common side-blotched lizard

(Uta stansburiana)

• Range: Western U.S. and northwestern Mexico

• Up to 2.5 inches, not including tail

• Brown, grayish or nearly black, with darker markings on back

• Adult males have blue, orange and yellow flecks on back. Females may have light and dark markings or white spots.

Black spot behind front limbs

“California Amphibians and Reptiles,” by Robert W. Hansen and Jackson D. Shedd

The Times was curious to see where people were spotting the three most frequently observed lizard species in Southern California, the fence, the common side-blotched lizard and the southern alligator lizard. As urban lizards go, it’s a bruiser, with bodies up to 7 inches long.

We analyzed nine years of iNaturalist records, along with data from the U.S. Geological Survey, and found that 63% of fence lizard sightings occurred in developed areas. The opposite was true of the side-blotched lizards, with 60% of sightings in natural areas.

The analysis was inspired by a 2016 Nature Conservancy report on Los Angeles’ herpetofauna. In a survey of the L.A. River, Pauly and colleagues found plenty of fence lizards in areas with woody shrubs along the riverbanks, as well as on the channel walls. But as researchers moved into the neighborhood, they found noticeably fewer fence lizards.

This isn’t all that surprising. In urban areas, there’s more concrete, less vegetation. Non-native plants don’t attract enough insects for them to eat.

“It’s just a hard place to live,” Pauly said. “We tend to not do a very good job of making our yards friendly to native wildlife.”

Between 2002 and 2014, blue bellies and two other common lizard species showed concerning declines in the Simi Hills surrounding Thousand Oaks and Westlake Village, according to a National Park Service study from 2021. Development, as well as the drought, may have put a squeeze on these populations.

Wildlife ecologist Kathleen Semple Delaney holds an adult male western fence lizard. In the background is a measuring and marking kit used to document reptile populations in the Santa Monica National Mountains.

(National Park Service)

Perhaps forced out of more natural areas by the other species, some fence lizards may have moved to suburbia, making trees and fences their preferred habitats.

Although a fragmented landscape isn’t ideal, even small pockets of space can help preserve biodiversity, said Kathleen Semple Delaney, a wildlife ecologist at the Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area.

“People don’t think of little hills as a conservation area, that they might not be important,” Delaney said. But they “can be important for lots of species, even lizards.”

How many reptile and amphibian species lived in the L.A. Basin before there were fences, house cats and roads?

Whatever that number was, said Hansen, a hardy subset remains.

“What qualities do those species possess that allow them to persist or even thrive in the face of development, while these other species blink out?” he said.

For Putman, who used to study rattlesnakes, fence lizards are a model for how animals handle rapidly changing environments. Fence lizards, unlike birds or large mammals, can’t travel long distances to more suitable habitat; they tend to live in the same place.

It appears that, like many who end up in the big city, some fence lizards develop street smarts. A collection of research by Putman and her students suggests fence lizards living in urban areas are more wary and vigilant than natural populations.

1

2

1. Western fence lizards can darken in warmer temperatures, sometimes appearing black in color. (Dania Maxwell / Los Angeles Times) 2. Fence lizards choose conspicuous basking places, such as tree trunks, rocks … and fences. (Dania Maxwell / Los Angeles Times)

Captive urban lizards showed more information-seeking behaviors, such as tongue flicking and head scanning. Another study found urban lizards were also more responsive to threatening sounds, such as a wildfire or a kestrel. They also tended to stay closer to their hiding places and were more likely to scurry away when approached.

At Westmont University in Santa Barbara and Cal Poly San Luis Obispo, Amanda Sparkman studied differences between blue bellies living near campus and those in more rural areas. In one paper, Sparkman used a makeshift “racetrack” — a four-foot enclosed wooden runway — to test campus lizards’ responses to people. Compared with wilder individuals, which ran away immediately, the suburban lizards would move away from the researchers in shorter bursts, but not entirely.

“They’ve adjusted to human presence to some extent,” Sparkman said. “It makes them sort of amenable to being watched.”

Sparkman warned against taking common species for granted.

“When something’s common, we think it can never go away,” she said.

The Sierra garter snake told us this is not the case. The species used to be everywhere in the Sierra Nevada, but during the last years-long drought, the population dropped “in ways we’ve never seen in 40 years of study.”

When Sparkman sees the easy-to-see blue bellies she’s filled with questions. How have they managed to persist in an urban environment? What is their future here?

“You can enjoy thinking about them and wondering about them,” she said. “Or just enjoy watching them do push-ups and chasing each other around. Either way is a legitimate way to enjoy these beautiful little creatures.”