Remember that time a natural gas field in the hills above the San Fernando Valley sprung a record-breaking leak, spewing 109,000 tons of heat-trapping methane into the atmosphere and polluting the air breathed by residents of L.A.’s Porter Ranch neighborhood with toxic chemicals, forcing thousands to flee their homes?

Gov. Gavin Newsom might prefer that you forget.

Newsletter

You’re reading Boiling Point

Sammy Roth gets you up to speed on climate change, energy and the environment. Sign up to get it in your inbox twice a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Early in his first term, Newsom talked a big game about working to shut down the Aliso Canyon gas storage field before 2027. More recently, though, he’s avoided acknowledging that pledge to Porter Ranch residents — even as his appointees prepare to vote next week on a plan that could keep Aliso Canyon operating into the 2030s.

If that sounds bad, well, strap yourselves in.

It’s been nine years since the gas leak, and eight years since lawmakers ordered state regulators to study closing Aliso Canyon, which is owned by Southern California Gas Co. Regulators finally released a plan last month.

But even after eight years of study, the California Public Utilities Commission didn’t reach a final decision.

Instead, the agency declared that closing Aliso Canyon will be possible only when the region’s gas demand falls to a certain level — likely not until the 2030s. And even then, Aliso won’t just close. Instead, the agency will open yet another regulatory proceeding to determine, yet again, whether the facility can really be shut down.

And who knows how long that determination will take?

“If they don’t set a clear goal, they’re just going to end up in the same situation five, 10, 15 years down the line,” said Denise Grab, a researcher at UCLA Law’s Emmett Institute on Climate Change and the Environment.

“This is bonkers,” she added.

Yes, it is. With Californians suffering more each year from deadly heat waves, destructive fires, powerful storms, punishing droughts and fast-rising seas, it’s unconscionable that state officials haven’t risen to the occasion.

And although it’s not entirely Newsom’s fault, he certainly shares the blame.

The Aliso Canyon gas storage field is nestled in the Santa Susana Mountains, along the northern edge of the San Fernando Valley.

(Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times)

In 2017, Gov. Jerry Brown’s administration called for Aliso Canyon’s closure by 2027. After taking office, Newsom tried to one-up his predecessor, saying he wanted to fast-track the 10-year timeline. He asked the Public Utilities Commission to expedite planning, saying the agency’s efforts may be insufficient to shorten the timeline.

That was November 2019. Since then, Newsom has abandoned his ambitious rhetoric.

Climate and public health activists are furious.

“If he’s truly committed to putting California on the forefront of climate leadership, he needs to follow through on his promise,” said Andrea Vega, an organizer with the environmental advocacy group Food and Water Watch, which has been running TV ads in Sacramento and the San Fernando Valley calling out Newsom’s inaction.

In some ways, the governor’s hands are tied by the fact that California is still hooked on fossil fuels.

Gas power plants supply one-third of the state’s electricity. Gas is also our primary means of heating and cooking.

In the L.A. area, SoCalGas uses its huge storage capacity at Aliso Canyon to keep prices down, buying fuel on the open market when demand is low and and stashing it at Aliso, a depleted oil field in the Santa Susana Mountains along the northern edge of the San Fernando Valley. SoCalGas then taps the stored gas when demand is high — in winter when people heat their homes, or in summer when gas plants fire up to power air conditioners.

State officials fear that if Aliso shuts down before Southern California has sufficiently reduced its reliance on gas, utility bills could skyrocket — especially for people who haven’t switched from gas heating and cooking to electric heat pumps and induction stoves. Or the region could find itself short on gas during a cold snap or heat wave.

Linda Serizawa, who was tapped by Newsom to lead the utilities commission’s Public Advocates Office, said state officials have to be “very careful about setting unrealistic expectations” when it comes to closing Aliso.

“We don’t want to keep the facility open any longer than it needs to be,” she said. “But it has to be reasonable.”

Newsom has been especially sensitive to concerns about energy reliability since August 2020, when two evenings of brief rolling blackouts affected hundreds of thousands of homes and businesses during a searing heat wave.

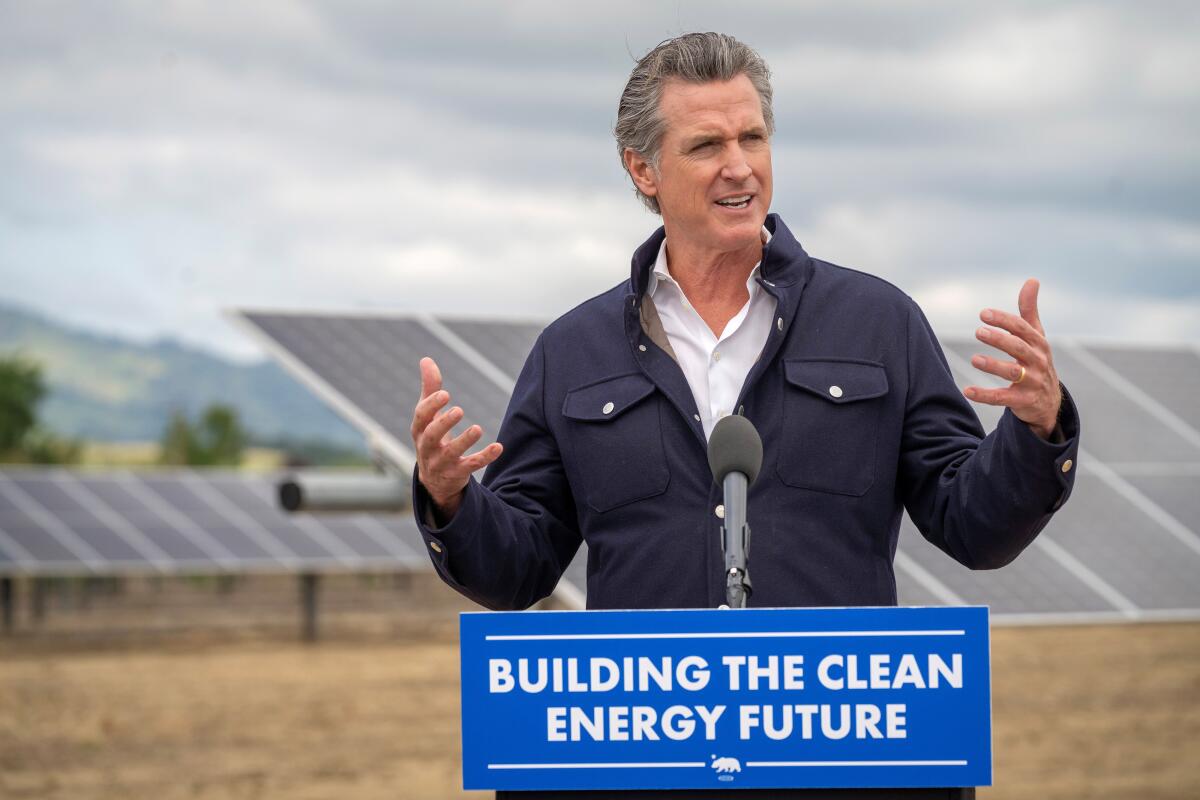

Gov. Gavin Newsom visits a solar energy and battery storage facility in Winters in April.

(Office of Gov. Gavin Newson)

There have been no repeat occurrences, in part because California is building giant batteries to store solar and wind power for after dark — a renewable energy success story, spurred by state climate policies. But that hasn’t stopped President-elect Trump from falsely claiming the state has had “blackouts all over the place.”

It also hasn’t stopped Newsom from extending the life of gas plants and other fossil fuel infrastructure, even at the cost of climate progress. Blackouts and high bills are wildly unpopular, even dangerous; if you can’t cool your home during a heat wave, you can end up hospitalized, or worse. Same thing if you can’t afford air conditioning.

“The Governor wants to see Aliso Canyon phased out, but not at the cost of enormous price spikes for working families and our ability to keep the lights on,” Newsom spokesperson Daniel Villaseñor said in an email. “It would be irresponsible to close [Aliso] before local demand for natural gas declines and the facility is no longer needed.”

When might that be?

The Public Utilities Commission’s plan, if approved by Newsom’s appointees at next Thursday’s meeting, would revisit the possibility of closing Aliso only when peak gas demand on the SoCalGas system is projected to drop to 4,121 million metric cubic feet per day. Right now, demand isn’t expected to fall to that level until at least 2031.

I asked Villaseñor if Newsom still supports shutting down Aliso Canyon before 2027. Although Villaseñor insisted that “the governor’s position on Aliso Canyon has not changed,” he ultimately didn’t answer my question.

Newsom’s quiet retreat is disappointing, because cost and reliability aren’t the only factors to consider.

Dozens of researchers from UCLA and other universities are studying the health fallout of the Aliso Canyon leak, which between October 2015 and February 2016 spewed a then-record 109,000 tons of methane. The $25-million study is being funded by SoCalGas and its parent company, Sempra Energy, as part of a legal settlement.

Although the study is several years from completion, some early findings are alarming.

“The [Porter Ranch] community has a lot of legitimate concerns,” said Michael Jerrett, an environmental health sciences professor at UCLA’s Fielding School of Public Health, who is leading the research.

Pregnant women living within seven miles of Aliso Canyon during the leak were 50% to 70% more likely to have low-birth-weight babies, Jerrett and his colleagues found. More recently, the research team determined that gas plumes likely stretched as far as 11 miles from Aliso — meaning more people could have been affected.

“The impact zone of the leak is considerably larger from what we thought it was,” Jerrett said.

A gas gathering plant sits on a hilltop at at Aliso Canyon.

(Jae C. Hong / Associated Press)

One reason the leak endangered San Fernando Valley residents is that the plumes didn’t just contain methane, a powerful planet-warming pollutant but not a significant air-quality threat. Nearby residents were also exposed to toxic chemicals, Jerrett said — one of the worst being benzene, which can cause cancer in humans.

During the gas leak, thousands of people reported headaches, nosebleeds, nausea and shortness of breath.

State officials and SoCalGas say they’ve worked hard to ensure the facility is safe to operate. In a fact sheet last month, the Public Utilities Commission said it has issued new safety protocols and conducted rigorous testing.

But when I asked Jerrett if he would live in Porter Ranch, his answer was “probably not.”

“In my household, I have people who have chronic respiratory conditions,” he said.

SoCalGas spokesperson Erica Berardi said in an email that the utility agrees with state officials that Aliso Canyon “is currently necessary to help keep customers’ electric and gas bills lower and for energy system reliability.”

Sucks for Porter Ranch residents. Nice for everyone else (minus the climate crisis).

“We’re one in a long line of pissed-off communities where cost-effectiveness runs into us,” said state Sen. Henry Stern (D-Calabasas), who represents Porter Ranch and has tried for years to shut down Aliso Canyon.

And here’s where things circle back to Newsom. It’s at least partly his fault we’re in this mess.

He’s been governor nearly six years — plenty of time to slash gas demand in Southern California. It would have been difficult, contentious work: paying people to replace their gas stoves with induction cooktops, for instance, and pushing the L.A. Department of Water and Power to lessen its dependence on gas-fired electricity. Newsom would have had to spar with SoCalGas, which has fought hard to safeguard its fossil fueled business model.

San Fernando Valley residents rally prior to an L.A. County Board of Supervisors meeting in 2020, calling for the closure of Aliso Canyon.

(Al Seib / Los Angeles Times)

Instead, Newsom sat on his hands. He watched while the Public Utilities Commission kept increasing the amount of fuel that SoCalGas is allowed to store at Aliso, while making little progress toward closing the facility.

Finally, after eight years of study, the commission’s latest plan endorses a portfolio of clean power resources to replace Aliso. But the agency doesn’t plan to issue any orders — like renewable energy requirements for electric utilities or incentive payments for clean stoves. Instead, it’s deferring action to other regulatory proceedings.

Frustrating, to say the least.

Also frustrating? When I asked why this is taking so long, a commission spokesperson laid some of the blame on SoCalGas residential customers, noting that they use more gas now than in 2015. Newsom’s spokesperson made a similar point, saying Aliso can’t close until “residents substantially reduce their natural gas consumption.”

Look: If you can replace your gas heater with an electric alternative, please do. Same with your stove.

But to blame regular people for Aliso Canyon is disingenuous — on par with oil companies claiming the climate crisis isn’t their fault, it’s everyone else’s fault for driving gasoline cars. The reality is, most people don’t have the financial means to break free from fossil fuels, not without supportive policy. We need politicians to step up.

If Newsom wants to prioritize closing Aliso, he can still change course. He can set a deadline and allocate political capital to making it happen. Maybe 2027 isn’t in the cards. But he can pick another date and stick to it.

Instead he’s hoping you’ll forget. You shouldn’t.

This is the latest edition of Boiling Point, a newsletter about climate change and the environment in the American West. Sign up here to get it in your inbox. Or open the newsletter in your web browser here.

For more climate and environment news, follow @Sammy_Roth on X and @sammyroth.bsky.social on Bluesky.