It’s Picasso season in Los Angeles.

Two terrific new exhibitions, one small and the other large, both unprecedented, answer the question: Is Pablo Picasso (1881-1973) overexposed in American museums?

In a word, no. Hugh Eakins’ recent book, “Picasso’s War: How Modern Art Came to America,” reminds us that the reigning titan of the Paris avant-garde wasn’t exactly embraced in the United States before World War II. Since then, he’s never been off the institutional radar screen. Yet if the curatorial framing is savvy enough, there is much to gain from looking again.

The exhibitions at Pasadena’s Norton Simon Museum and the UCLA Hammer Museum in Westwood are both firsts, which is fairly remarkable for an artist so abundantly studied.

The small show is “Picasso Ingres: Face to Face” at the Simon — just two paintings, roughly the same size, both killer. The pairing was organized by Christopher Riopelle, curator of London’s National Gallery, where it was seen during the summer, and Simon chief curator Emily Talbot.

For the first time, Picasso’s riveting 1932 “Woman With a Book,” acquired by the late Norton Simon in 1960, hangs next to the extraordinary picture whose composition the Spaniard adapted for his own — in a manner both affectionate and brash. Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres’ 1856 “Madame Moitessier” is one of two portraits the artist did of Marie-Clotilde-Inès Moitessier, a woman he called “la belle et bonne” — the beautiful and good.

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, “Madame Moitessier,” 1856, oil on canvas.

(The National Gallery, London)

The Ingres, an incomparable National Gallery treasure never before seen in California, is a sumptuous extravaganza, a portrait of a wealthy merchant’s wife dressed in silk marked by an opulent floral pattern, a hair ornament of intricate white lace and a cascade of pink satin, plus chunky, eye-popping jewelry. A painted fan is tucked beneath her left hand, and she is surrounded with furnishings that signify her upper-class bourgeois affluence, about which her slight, soft, “Mona Lisa” smile suggests she is mighty pleased.

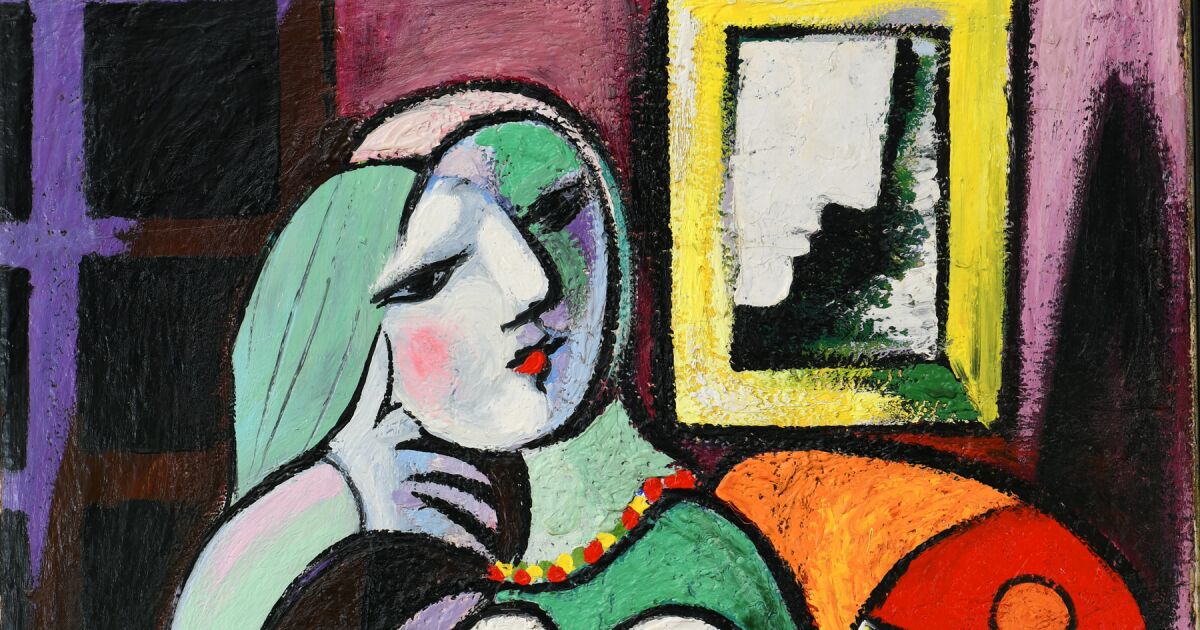

The Picasso is one of an extraordinary group of 1932 portraits of Marie-Thérèse Walter, the artist’s much younger lover. (She was 23, he was 51.) Like Moitessier, Walter wears a floral dress and is seated in an upholstered chair. Likewise, her head is shown in three-quarter view, not exactly resting on a raised right hand. Its index figure taps at her temple to evoke the Classical pose of the goddess of Arcadia in a famous Roman fresco from Herculaneum.

Fingers on both women’s raised hands are without skeletal structure, languorous and at ease. Behind Walter, a framed picture of a profile head echoes the mirrored head behind Moitessier in Ingres’ portrait. There are no glamorous furnishings — just a French window, its blackened panes suggesting the dark of night.

Beyond these general similarities in composition, the tenor of the paintings couldn’t be more different. Moitessier is majestic, Walter humbler. Moitessier is swathed in luxe floral fabric with fashionable bare shoulders, Walter in a folkish blouse with puffy sleeves, provocatively slipping to her sides. Moitessier is elegantly proper, Walter is disheveled, breasts popping out of a see-through bustier.

Most tellingly, Moitessier’s closed fan is now an open book, which Picasso moved from the side into a central position in Walter’s lap.

The V-shaped pages flutter in her similarly splayed fingers, creating a startling double image suggesting masturbation. (The act goes unmentioned in the otherwise fulsome exhibition catalog, which is as chaste as Mme. Moitissier.) It takes its place with other rapturous 1932 Walter paintings, including the fellatio underway — complete with a hint of castration in her dagger-like tongue — in “The Dream” and the delirious bondage scene in “Nude, Green Leaves and Bust.”

Related masterpieces by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, left, and Pablo Picasso had not been shown together before.

(Christopher Knight / Los Angeles Times)

The Picasso is a sex painting, the virtuous Ingres’ emphatically is not. Which raises the question: What did the Spaniard see in the Frenchman’s masterpiece, which he had encountered much earlier in a celebrated 1921 Paris exhibition, that drew him to use it for a very different painting? For me, one answer is in the optics.

Ingres spent 12 excruciating years getting every exquisite detail down in his portrait. Some think he employed a camera lucida’s lens to render sitters as accurately as possible, which makes two details surprising. Those boneless fingers by her face serve multiple functions, implying her erudition in the Arcadian reference and her accustomed leisure in their languorous droop. And the mirror reflection is optically wrong, recording Inès Moitissier in profile — which is impossible.

That’s probably what got Picasso interested.

He’d paid attention to Ingres since his youth, and the older painter’s intensely observed naturalism was always convincingly manipulated to achieve expressive ends. If the mirror reflection didn’t line up with visual reality, that was secondary to his desire to frame and flatter his subject as if she were an empress on an ancient Roman coin.

Picasso turned that mirror profile into a painting that hangs on the wall behind Walter. It too is a Roman style head, but it fuses his and his lover’s profiles, now hovering over her together as she pleasures herself. The erotic psychological probing in Surrealist painting meets the visual intimacy inherent in Picasso’s Cubist invention, in which multiple sides of an object are seen at once, just as they would be if held close to a viewer’s eyes.

Try it yourself: Next time you passionately kiss someone, keep your eyes wide open; your lover’s features will shatter into multiple, fragmentary perspectives, seen all together. Now look at Walter’s face, seen frontally and from the side at once. What the eye sees was as important to Picasso as it was to Ingres.

Picasso finished his brash painting in just a few days. It’s almost an abrupt, indelicate retort to Ingres’ laborious refinement. (The surface of the latter’s is even highly finished and smooth, while the former’s is rough and coarse.) Through imitation Picasso registers profound admiration for Ingres, all while taking possession and making the portrait his own.

Pablo Picasso, “Head of a Woman,” 1961, graphite on cut and folded paper.

(Christopher Knight / Los Angeles Times)

Across town at the large Hammer show, a smashing survey of an unexpected body of work unfolds — literally. For the first time, “Picasso: Cut Papers” assembles about 100 examples of works on — and in — paper incised with scissors. Think of it as a pop-up show with three-dimensional objects, most modestly scaled and made from folded paper.

The earliest — charming silhouettes of a dog and a dove — date from about 1890, when the precocious artist was 9. The observational inventiveness is riveting, especially in the dove, the curved contour of its closed wing made through a simple, narrow cut from his Aunt Eloisa’s petite embroidery scissors.

The latest are 1962 collaborations with photographer André Villers, made when Picasso was in his 80s. (He died at 91.) Cutouts and fabrics were laid on camera-free photographic paper exposed to light, yielding a layered, alchemical vision of ethereal landscapes, musicians and portraits.

The show opens chronologically, lining up 15 works made through the 1910s, which lay out most of the variety of approaches he would take in the next seven decades. After that, the cut papers are installed in revealing ways that reverberate with one another.

We associate cut paper with Matisse, whose scissors made astonishing forms from vivid color. By contrast, the 15 introductory Picasso works culminate in a dazzling little brown-paper construction of a guitar resting on a table before a window. It’s less than 7 inches high. Negative space and positive materiality interpenetrate in an extraordinary formal condensation of Cubist technique. It evokes Picasso’s nearly life-size sculpture study, “Guitar” (1912) , not in the show but a pivotal moment in the Cubist revolution.

Pablo Picasso, “Head,” 1943, torn and burned paper.

(Musée National Picasso, Paris)

Speaking of the installation design, it’s exceptionally beautiful. Paris-based Agence NC Nathalie Crinière has centered a dark blue-gray square room inside the mostly white square gallery, with cutouts piercing all four corners to layer views into inside and outside spaces. Some objects are in shadowboxes, while many flat sheets are placed on tilted shelves, which reach out to make for easy viewing. The elegant design is articulate and generous.

Curators Cynthia Burlingham, director of the UCLA Grunwald Center for the Graphic Arts, and Allegra Pesenti, former associate director there and now independent, have grouped works in loose categories, most based on fabrication techniques: silhouettes, torn and perforated papers, pinned and pasted, etc. (Their catalog is excellent, an essential addition to voluminous Picasso scholarship — no mean feat.) Bernard Ruiz-Picasso, the artist’s grandson, and his wife, gallerist Almine Rech, and the Picasso museums in Paris and Barcelona are principal lenders. Most of the works have been tucked in flat files for years, which kept them pristine and makes for a rare and surprising opportunity now. (The show will not travel.)

A small number of the sculptures are made from folded sheet metal — a toy horse, a chair, a mother and child — which recalls the construction of many monumental Picasso sculptures. A sense of obsessive, curious, voracious playfulness runs throughout the exhibition. It’s a spirit that is certainly related to, yet distinctly different from, the bawdy bandying that unfolds in Pasadena.

Picasso, times two

Norton Simon Museum: “Picasso Ingres: Face to Face,” through Jan. 30; closed Tuesdays and Wednesdays. 411 W. Colorado Blvd., Pasadena. (626) 449-6840, nortonsimon.org

UCLA Hammer Museum: “Picasso: Cut Papers,” through Dec. 31; closed Mondays.

10899 Wilshire Blvd., Westwood. (310) 443-7000, hammer.ucla.edu