In the last couple of years, the Los Angeles Unified School District, the Los Angeles County Office of Education and the state of California have affirmed their commitment to climate education for all students, pre-K through 12th grade. In October, Gov. Gavin Newsom signed Assembly Bill 285, requiring climate education for all public school students starting in the 2024-25 school year.

Los Angeles-area public schools are now guided by the country’s most ambitious climate education policies, according to local school administrators and advocates for environmental education.

There’s just one problem: There’s little additional money for any of it.

Tired of waiting for politicians to step up with funding, some teachers are investing personal time and talent to create their own climate lessons and raising funds for green initiatives on their campuses.

1

2

3

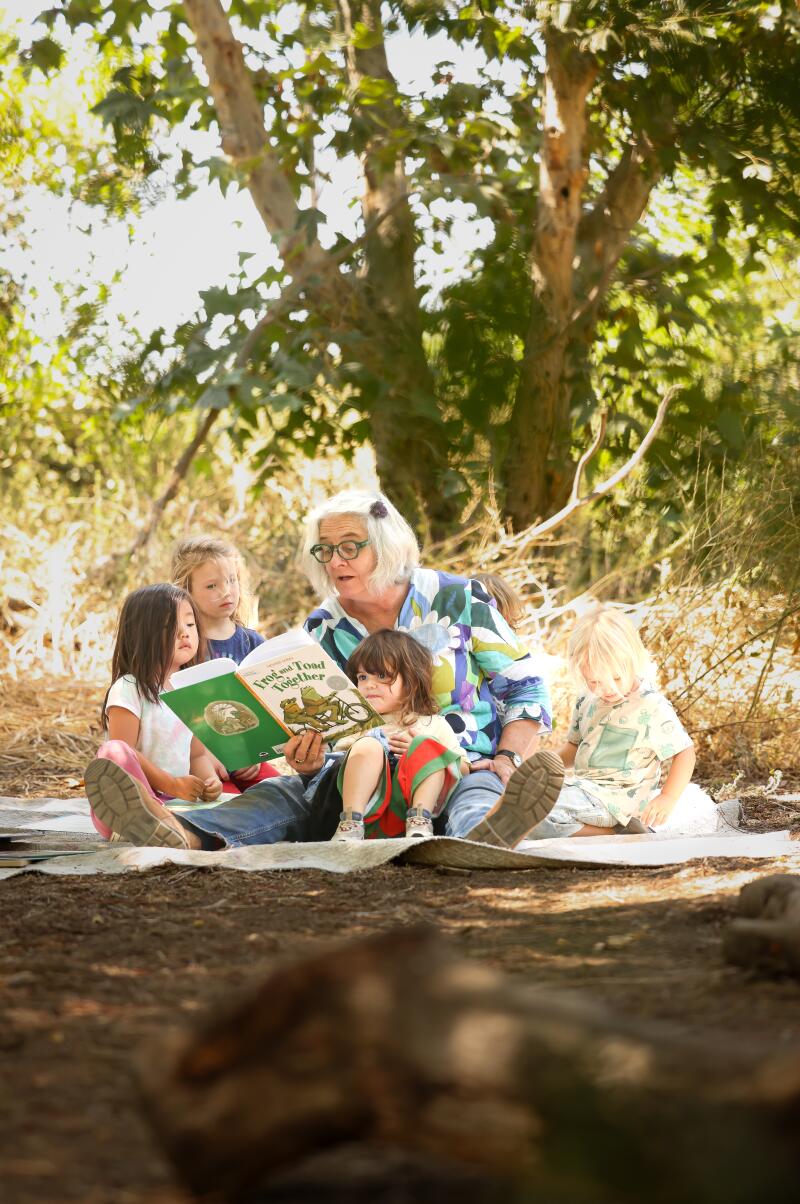

1. Angela Capps leads kindergarten students on a hike at Earthroots Field School in Silverado Canyon. (Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 2. Teacher Arturo Romo shows student Jason Aviles, 17, how to harvest basket making material from a native habitat area at Sotomayor Arts & Sciences Magnet. (Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 3. Fabienne Hadorn, co-founder of Arroyo Nature School, reads to the children in South Pasadena. (Christina House / Los Angeles Times)

Within the Los Angeles Unified School District, these teachers are often tapped to be “climate champions.” Principals at each of the district’s roughly 1,220 schools are to pick one teacher who will receive $900 a semester to help other educators on their campus create climate-centric lessons.

A statement from LAUSD says: “Through the school’s Climate Literacy Champions and all classes, including science, students learn about climate change by tackling real-world problems connected to the 17 United Nations Sustainable Development Goals.”

The “champions” get together regularly to support one another and share ideas and work with their principals to encourage other teachers to join the effort. But some of them say it is a daunting responsibility, adds to an already heavy workload and can lead to burnout.

Implementation of the climate literacy policy “has been spotty,” said Lucy Garcia, a former LAUSD teacher who was a principal author of the resolution. “Nothing happened the first year. The second year they only trained 145 champions. We need more to happen faster in classrooms.” Currently there are a total of 314 champions.

Frances Baez, the district’s chief academic officer said that “there is universal support for climate literacy” at LAUSD, adding, “We do not have the funding to reach the scale we all want to achieve.”

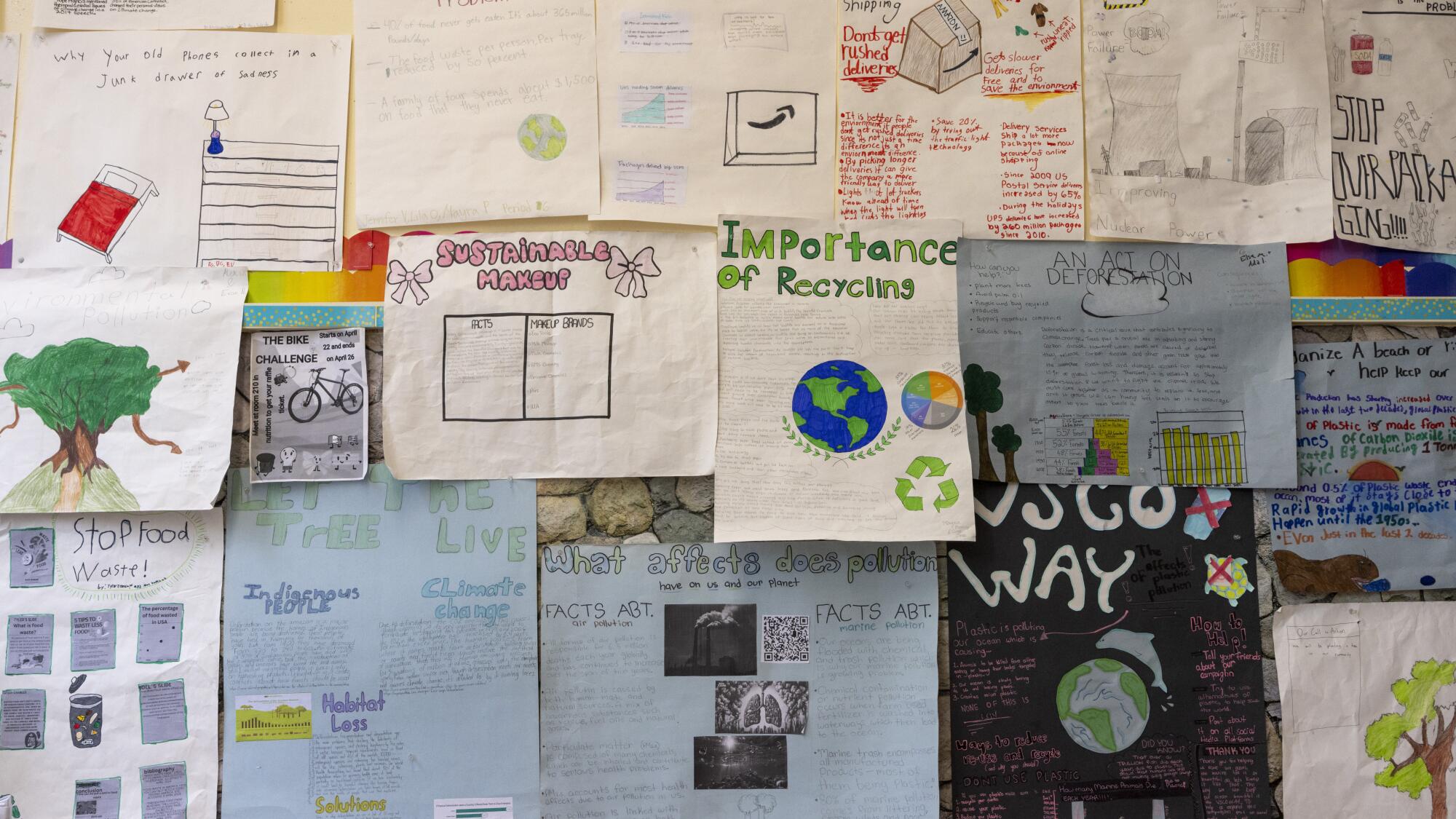

A classroom wall at Mark Twain Middle School is dominated by environmental concerns.

(Zoe Cranfill / Los Angeles Times)

Baez encourages teachers to seek support from nonprofit education funders. A favorite of hers is Esports for Good, which offers a “Minecraft” video game based on the United Nations’ sustainability goals. Students create virtual solutions to real-world climate problems.

Individual schools have found support for climate programs from private foundations and federal and state grants.

One of the leading nonprofits in this field, Ten Strands, is the force behind the California Environmental Literacy Initiative, a centralized effort to press state and local education leaders to fulfill their commitments.

The network of educators, public school administrators, local and state agencies, and nonprofit partners provides resources, curriculum and professional support to one another. “Everyone in the state doing this work is singing the same song as one choir,” said Andra Yeghoian, the initiative’s project director and Ten Strands’ chief innovation officer.

“Climate literacy is not taught in isolation, and it’s not taught every single day, and it’s not taught all day long,” Baez said, adding that the goal is to integrate it into all learning. “We are definitely not where we want to be, but we’re getting there.”

When it comes to greening campus energy technology, the potential for change is far more promising. It’s one area with a large pot of readily available federal funds through the Inflation Reduction Act.

Federal rebates can cover 30% to 50% of the cost of solar energy, energy storage technology and high-efficiency heat pumps. Grants and more rebates are available to electrify school bus fleets and install charging stations.

Students plant green onion, basil and kale at 24th Street Elementary School’s garden in Los Angeles.

(Christina House / Los Angeles Times)

“The new federal money for upgrading the climate resiliency of our schools is real and significant,” said Jonathan Klein, co-founder and chief executive of UndauntedK12, a national advocate for sustainable, healthy schools.

LAUSD’s chief eco-sustainability officer, Christos Chrysiliou, is in charge of capturing these dollars to fulfill the district’s commitment to switch to 100% clean electricity by 2030 and clean energy in all sectors, including transportation, by 2040.

One sign Los Angeles should benefit from this program was Chrysiliou’s appearance on the dais at last spring’s White House conference touting President Biden’s investments in sustainable schools.

Two other potential new sources of money to enhance climate education and school infrastructure — gardens, outdoor learning spaces and other facility enhancements — will be on the November ballot in California.

Proposition 2 would authorize the state to borrow $10 billion to construct and modernize school facilities, and Proposition 4 would authorize the state to borrow $10 billion for climate programs including clean water, wildfire, forest and sea level rise projects.

The propositions are real progress, said Mikaela Randolph, who runs the Southern California Leadership Institute of the nonprofit Green Schoolyards America, whose goal is to expand tree canopies to cover at least 30% of every school campus nationwide, enough to reduce campus temperatures, according to the group’s research.

“Dedicated funds to move this work forward is an opportunity to re-envision our schools,” said Randolph, allowing outdoor learning while protecting students from the effects of climate change.

Kids learn about the environment at a camp operated by Earthroots Field School in Silverado Canyon. Many educators like to take their lessons on the environment outside.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

Chrysiliou said he can’t wait for funding and is moving ahead to develop a “road map” for climate literacy education and engagement, construction, operations and maintenance embracing social equity and inclusion.

“Outdoor learning is extremely important,” he said. “Research shows students can learn so much from nature. We’re looking to develop spaces that are more intriguing to our students, more exciting.

“There’s a great interest from our students in climate change. Our cities have been transformed into asphalt and concrete urban environments. Our students don’t want that at their schools. They are eager to learn about farming, about plants, to experience nature at school,” he said.

Our Climate Change Challenge

Creating their own curriculum

California wants climate education for its students. Meet some of the teachers, schools and nonprofits making it happen.