“My personal opinion is that if the ball’s hitting the stumps, the ball’s hitting the stumps. They should take away umpire’s call, if I’m being perfectly honest. But I don’t want to get too much into it, because then it’ll sound like we’re moaning that that’s why we lost.”

Make what you will of Ben Stokes‘ remarks about the DRS at the end of the Rajkot Test. On social media, however, more than a few observers have heard the moaning far more loudly than any justified indignation, at the end of a Test in which his team had been comprehensively thrashed.

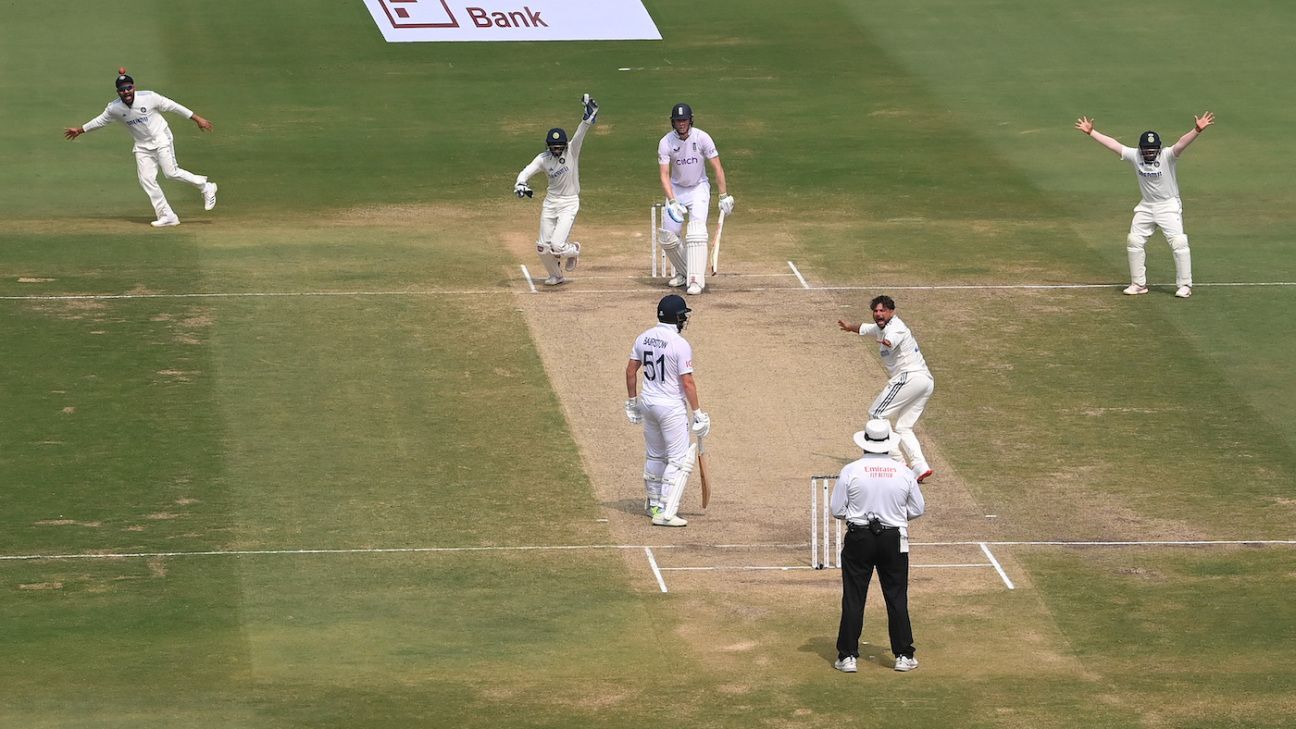

Stokes did go on to clarify that the technology was not the reason for England’s defeat. Yet it’s indisputable that they were on the wrong end of a series of extremely tight DRS calls in the course of the contest – most particularly Zak Crawley‘s in the second innings, which was shown as such a marginal flick of the leg bail that the TV graphic didn’t even align to the data returned by Hawk-Eye.

Such were the reasons why Stokes and Brendon McCullum approached the match referee Jeff Crowe at the end of the game, to seek clarification about a system that, as McCullum subsequently admitted to the UK media: “I don’t really understand, to be honest… it’s a little hard from a layman’s point of view to understand how it works.”

Either way, the genie is back out of the bottle, now that England’s captain has cast aspersions on a system that is far more deeply nuanced than the binary arguments that invariably follow it around. Virat Kohli did much the same on England’s last tour of India in 2021, when he suggested that umpire’s call “creates a lot of confusion” – a remark that led directly to the ICC recalibrating the wicket zone from the bottom of the bails to the top.

Who knows whether Stokes’ remarks will have a similar upshot, but it’s another damaging blow to a process that effectively protects players from the justice they think they are seeking. Nobody could ever claim that DRS is a perfect system, and it’s pointless to deny that it had an eyebrow-raising few days in Rajkot. But when it comes to the unique issue of lbws, and their reliance on incomplete information, umpire’s call offers a shade of grey when neither black nor white is appropriate for the process the players are undergoing. For the most part, it spares the sport from exactly the sort of flashpoint that we’re dealing with now.

We are, after all, talking about the likelihood that, when stopped in its tracks some six feet from its target, a piece of leather with a diameter of approximately 2.8″ would have struck a 28″ x 9″ stack of sticks with sufficient accuracy to dislodge either of two wooden bails that protrude a further 0.5″ above the height of the three stumps themselves – an anomaly that might well have accounted for the misrepresentation of the aforementioned Crawley dismissal.

And so, to go back to Stokes’ initial assertion – “if the ball’s hitting the stumps, the ball’s hitting the stumps” – what does that actually mean?

If we take his remark at face value, and assume that Stokes believes that even the faintest nudge on the stumps should count as a dismissal, that would in essence leave batters defending a target area of close to double the actual dimensions of the wicket – around 450 square inches instead of 252, given the additional area created by the ball’s diameter on three sides.

And yet, in a serendipitous incident on the 2021-22 Ashes tour, Stokes himself became the living, breathing manifestation of the need for a margin of error in decision-making. Facing up to a delivery from Cameron Green during the Sydney Test, he was given out lbw by the on-field umpire Paul Reiffel but successfully overturned it when replays showed that the ball had missed his pad but clipped his off stump without dislodging the bail.

And so, to take it to the other extreme, if Stokes was suggesting that only balls that would be completely smashing the stumps should be considered for lbws, then that target area would plummet to little more than the dimensions of the middle stump itself (86 square inches, since you asked), and the sport would revert to the pre-DRS days when batters were permitted to park the front pad with impunity and bore fingerspinners in particular out of existence.

Clearly, if umpire’s call were to be abolished, those parameters would need to be set at some mutually acceptable point in between those two extremes. But that wouldn’t resolve the fact that the target area of the stumps would be arbitrarily and permanently expanded – by close to 100 square inches even for a 50% impact – nor that there would have to come a point on the very limit of that margin, as with the flicking of a light-switch, when light turns to dark and you’re faced with the complete reversal of any given decision.

England, ironically, discovered this the hard way in the second Test in Visakhapatnam, when Crawley, again, was the victim of a contentious lbw – this time a leg-stump-adjacent delivery from Kuldeep Yadav that looked to be sliding down, but was projected to be hitting enough of the stump to overturn the on-field not-out verdict.

And that exception arguably proves the rule as to why umpire’s call is a vital factor in expectation management. As we’ve seen in football since the advent of VAR, the 180-degree decision U-turn is the single most frustrating aspect of technology’s introduction. It’s not an improvement to kill the passion of the moment by putting all emotions on pause until the all-seeing eye has had its final say, especially when the verdict is overturned by the skin on a defender’s knee, or the stitch of a cricket ball’s seam.

Absolutists will still argue that you should trust the technology – if it’s good enough for missile guidance, then it’s clearly an improvement on the umpire’s all-too-human eye. But that argument misses the point on several levels.

Firstly, it ignores the fallibility that exists even in machines – tennis has successfully incorporated Hawk-Eye for line calls, and has the benefit of being able to replicate the full path of the ball in each disputed case. But at Wimbledon in 2022, to cite one example, the US player Rajeev Ram refused to play on after querying a tight call. “We’re turning the machine off,” he demanded. “We’re not in the future here, man.”

Secondly, and most importantly, the crucial point about DRS itself has never been to extract absolute truths about dismissals, but to do away with gross injustices. Clear howlers, such as Alec Stewart’s infamous lbw against Sanath Jayasuriya in 2000-01 that pitched six inches outside leg, are quietly and effectively dealt with these days. As indeed are all manner of inside-edges into the pads. The issues that kick up a stink are those that fall precisely on the margin of in and out.

Clear 50-50 calls, in other words, that always have and always will fall into that sweet spot of contention, and every now and again blow up irrespective of any attempts at mitigation. It’s surely preferable, in such instances, for an on-field decision that guides the emotions into the resulting review, even if – in Crawley’s case – the upshot isn’t quite what the aggrieved team is hoping for.