We all have an inner clown, a wild self whose yearning for delight is greater than the fear of failure. A little one who wants to play during nap time, convenience to others be damned. Underneath layers and layers of socialization, we each have a clown willing to risk heartbreak for joy. Or at least that’s the idea.

Clowning, an ancient art form that includes but is not limited to the red wigs and big shoes of the circus, is difficult to define. Filed under “physical comedy,” a clown communicates primarily through their body rather than words.

Yulissa wears Balenciaga jacket and skirt, talent’s own shoes.

All I’m sure of is that without an audience — to play with, to laugh or not laugh, and hopefully cry and transform — there is no clown. I’ll admit: When I started, I wanted the benefits of clowning, namely feeling comfortable and even coming to enjoy reading my work in public, without any of the scary bits (and clowns in America have quite a scary reputation). I had asked my first clown teacher for private (read: audience-free) lessons. She chuckled over the phone: “It doesn’t work that way.” Thus began my fool’s journey, if you will, from scared and lost to scared and lost with a dash more openness to being vulnerable.

I was glad I was wearing sneakers because I ended up running from the subway station to the midtown Manhattan building. I arrived at Room 315 on time and out of breath. It was a Saturday, and I was there for a two-day workshop, from noon to 5 p.m., with an hour break for lunch, with Christopher Bayes. His credentials, in a field where it feels funny to have them, include studying under clown masters Philippe Gaulier and Jacques Lecoq and working as the head of physical acting at Yale’s David Geffen School of Drama. While this all sounds technique-heavy, Bayes is known for valuing a heart-forward approach over an intellectual one. This was an honor for which I somehow justified paying $300.

We began with introductions — names, pronouns, why we were there. “I’m a writer,” I said, picking one job, out of the three I had, most suited to the moment. “And I’m writing a piece on clowning.” I scanned the room and my eyes landed on A, whom I recognized from another workshop. Our faces lighted up. We smiled — and clowns must smile only when they’re actually happy since, as I learned in workshop, a smile is a mask — and waved to each other. When it was A’s turn, they explained that whatever they were seeking from psychoanalysis, they were finding in clowning.

In this group of about 25 people, there was also a theater director who flew all the way to New York from San Francisco to take this workshop. There were a lot of people who loved theater and hoped a more honest connection with audiences would bring them back.

Next were the warm-up exercises. We started shaking our bodies, and I made another mental note: Actors and musicians all did warm-up exercises. What was the equivalent for writers? My thought was interrupted when Bayes instructed us to laugh very hard. It had been a confusing week, a mix of macro tragedy and micro wins. I cracked up, and it felt like sobbing. The group entered a frenzied state. I acclimated to the cacophony of primal sounds. We sounded like the animals we tend to forget we are.

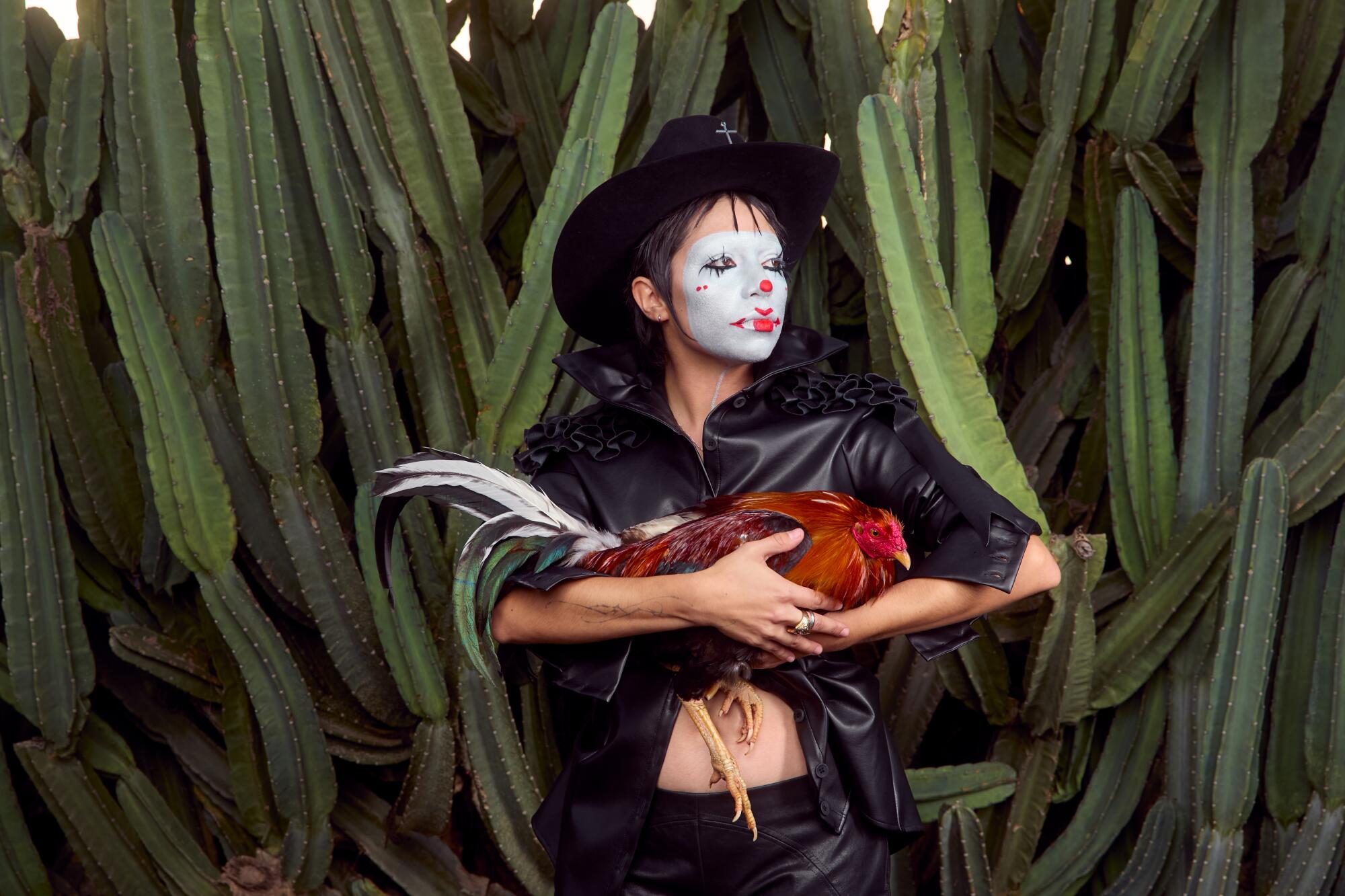

Yulissa wears Rio shirt and vest, Elena Velez pants, Pskaufman… shoes.

“Now cry!” Bayes shouted. I wailed and made my ugliest face. I was screaming so loud my voice cracked and I had to cough to clear it. I said, “Why, oh why?” I slapped my hands down on my quads. I headed toward the floor. I curled into a ball and cried with my face hovering an inch above the wooden floor. I heard a voice from above: “Don’t hide your sadness.” I stood up awkwardly having just been reprimanded for crying the polite way. I needed to cry the clown way, that is, take up space. I balled my hands into fists and stretched my arms out and up. I turned my face toward the ceiling and blamed it for all that was wrong with the world. Sobbing from the belly and feeling like some sort of tragic figure, I doubled over in laughter and now I couldn’t tell the difference between the two.

Afterward, we separated into groups of four. We were given 10 minutes to devise a song, along with a dance. My group chose the chorus “I love it.” We all had solos when we sang about something we genuinely loved. I sang about my apartment, how I loved it. I got the instructions mixed up and tried to rhyme but learned I wasn’t supposed to, so I sang, “Ohhhhhh, that’s easieeeeerrrr.” My solo came to a dark end: I loved my apartment, but I couldn’t afford it on my own, without roommates, and even if I could, it would be selfish to live there alone because of the city’s housing crisis. I sang about how the rental vacancy rate was 1.4% and that 5% was considered an emergency. There was nowhere else to go, so I sang to the audience to think about that. Some of the faces in the audience looked scared. My group sang, all together, “I love it, I love this love, I love love love love, yeah I like it!” We broke for lunch, and someone added me to the “Clown NYC” WhatsApp group. It has 712 members, and there are multiple threads, including “Shows & Mics,” “Meetup & Hangouts,” “Prop/Costume Exchange” — and “Housing.”

When I saw my first clown show, Julia Masli’s “Ha Ha Ha Ha Ha Ha Ha,” my first words might have been, “What the f—?” Masli emerged on a blueish dark stage amid the haze of fog. I recall a Medusa-like nest of wires around her head with a light illuminating her face. A gold mannequin’s leg with an attached microphone substituted as Masli’s left arm. She was bundled in a witchy outfit resembling a duvet cover. Masli looked extraterrestrial, complete with the wide, innocent stare of a being looking upon our society and its problems from a fresh perspective.

As a clown, it’s ideal if you wear something so stupid, people laugh just glancing at you. A performer’s costume signals to the audience that they’re in a space operating outside of societal norms, a place of amplification. While a clown’s “look” can be idiosyncratic and interesting, what starts off as funny and absurd gives way to the profound. In this way, clowning appears light and gets deep. With the support of aesthetics, a clown communicates, “Isn’t being human with all of its striving for status and repression in order to fit in kind of ridiculous?”

In “Nothing Doing,” a work-in-progress, clown Alex Tatarsky announced at the top that they didn’t believe in work or progress. They entered the stage in a top hat, white sequined leotard, rhinestone heels, sporting a long, thick braid attached to their hair. When they turned around for the first time, I was treated to a grotesque mask at the back of Tatarsky’s head and prosthetic cleavage that might have also been the plastic molding of butt cheeks. By the close of their show, after having mimed chasing after the performance’s nonexistent plot, Tatarsky sat at the head of a table, facing the audience, eating Life cereal with milk, with their hands, out of an empty skull, and at one point chewed and swallowed a cigarette. They said something like, “Darling, I just want you to love me, but it’s repulsive when I’m this desperate.” This desperation, rather than repelling me, became a source of connection. I found myself falling in love with this clown and, in turn, with the parts of myself I tend to reject.

Yulissa wears Willy Chavarria shirt, Rio skirt, Pskaufman… shoes.

In the environment of a clown workshop, practicing loss of control (a clown can’t plan for an audience’s response) and being present with what is (a clown works with whatever they’ve got) can feel good. One eases off expecting specific results and being disappointed when things don’t turn out according to a rigid vision of success and delights in surprises no one could have imagined. If clowning is on the rise, and it certainly feels that way, it might be because it provides relief from having to keep it together.

On the second day of the workshop, we tried a different exercise. Two conventionally attractive men were onstage, and I was prepared to hate them both. Why? Because conventionally attractive men send me hurtling back in time to when I was an awkward preteen, and I’ve since developed an aversion. Bayes instructed them to get to know each other. They looked uncomfortable. One extended a handshake to the other. The crowd booed at the predictably masculine, business-like gesture. Then, Bayes told them to turn away from each other and walk to opposite ends of the room. One faced stage left, the other stage right.

They had to jump around to face each other and land at the exact same time. They kept failing. “Oh, come on,” I jeered. Ten minutes passed. The audience was exasperated. An eternity passed. One would turn around while the other didn’t move. Was I cursing them somehow? One wore a crisp white T-shirt that looked expensive with black wide-leg trousers. He had shoulder-length hair parted down the middle, like a model. The other, a white T-shirt that looked worn-in, black joggers and a delicate hoop earring. Both were barefoot. They kept missing even though they could technically cheat and set a pattern for the other to follow. It was agony. Bayes, who was sitting next to me, drew my attention to the man on the right. He was twitching. His eyebrows, his legs. The impulses were all confused. I laughed. I thanked the heavens that my performance of the same exercise didn’t go this badly.

Bayes told them, “You’re not getting it because you haven’t tucked in your shirts and raised your pants all the way up.” The two clowns followed the instructions. Now, they looked more ridiculous and endearing. We waited. We breathed. Finally. They jumped. They landed at the exact same time. People erupted in applause. A great tension was released. I rose from my seat along with others for a standing ovation. No matter how hopeless it seems, a clown can always win back the audience.

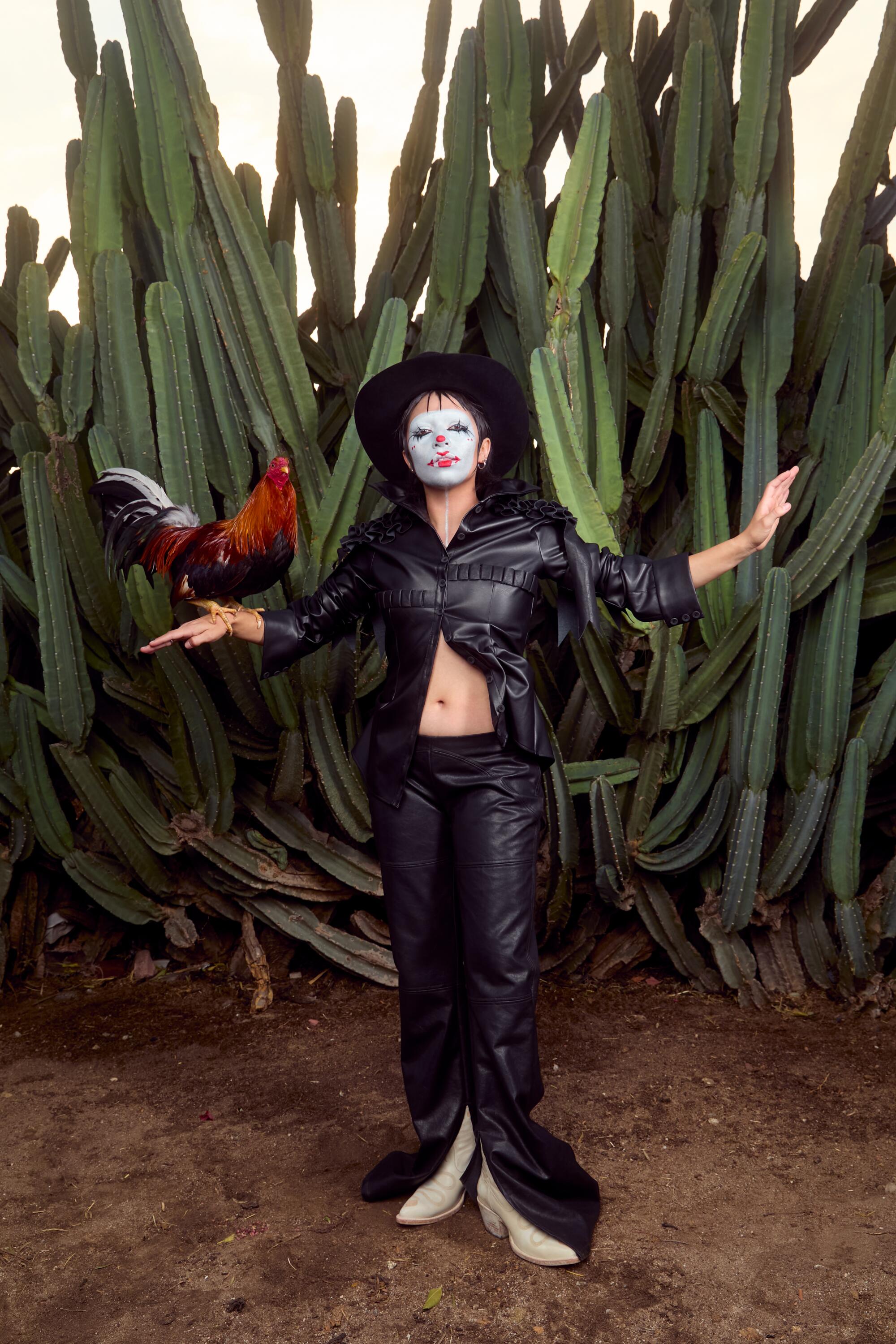

Yulissa wears Elena Velez shirt, pants, and hat, Pskaufman… shoes.

Now, the two men were facing each other. There were more boos. They lost us because they were “trying” again. I joined in, feeling like I was at a wrestling match where I wanted neither party to win. Now they were holding hands and squatting up and down vigorously. “Say, ‘Oh, yeah,’ ” shouted Bayes. They complied in unison. “Now say, ‘Oh, daddy,’ ” Bayes shouted. Again, the two complied, but they missed a beat and now they were saying “Daddy, O” in a guttural way as they continued holding hands and squatting up and down. I was laughing hard and clapping my hands. I was full of glee. In less than 30 minutes, I’d seen myself mirrored and altered. I could be someone who was afraid of being in front of others. Cocooned in the safety of a crowd, I could be cruel. I could be extravagantly generous. The clown wanted my love regardless. The clown was there to hold it all. I learned things that words fail to capture.

You had to be there. And that’s what I love most about clowning — it brings you into the now. Everything else fades away. It’s no longer about the shape something takes but about the attempt. No one is ever done as a clown.

Later that week, I found myself singing a stupid-sweet song from the workshop called “Open Like a Little Flower.” The next line was “Open like a different type of flower.” I remembered Bayes saying that when you go looking for beauty, you find it. I remembered too my pounding heart. Breathing hard from physical exertion. Buzzing with the high of a collective response, with the feeling of wholeness.

Priscilla Posada is a writer living in New York City. Her work can be found in the Los Angeles Review of Books, BOMB and the Brooklyn Rail, among other places.

Photography & Talent Yulissa Mendoza

Styling Erik Ziemba

Hair & Makeup Jaime Diaz

Art Direction Jessica de Jesus

Production Alexis de la Rocha

Photography assistant Lily Soleil Lewites

Styling assistant Nathan Alford

Content assistant Perry Picasshoe

Special thanks Ricardo Mendoza